The Invisible Injury

About the TBI I sustained. It's a bigger part of my life than I'd like. This is a longer one. If you were hoping to read about fish or birds, plenty to come.

Preamble: April 20, 2023.

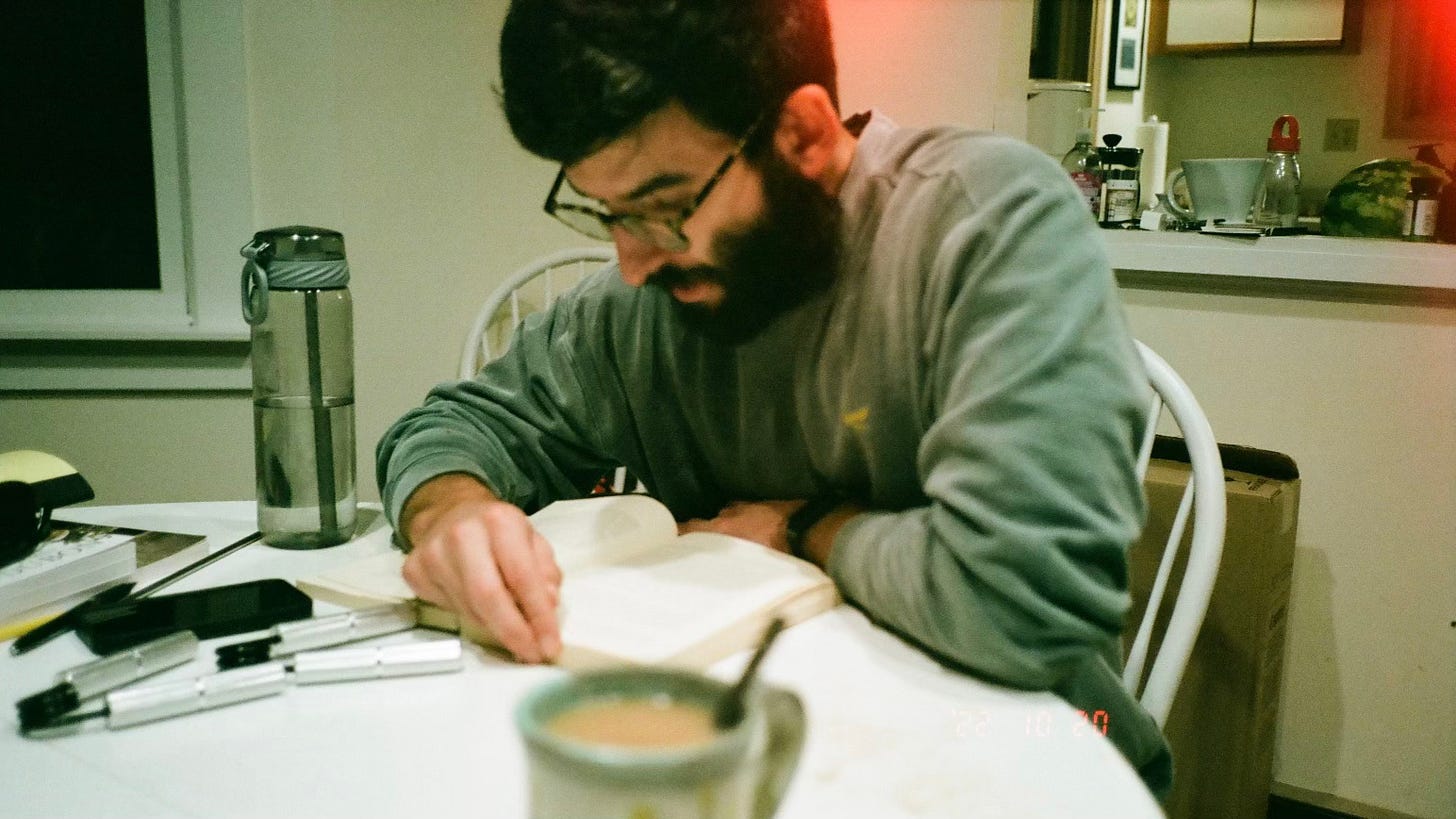

I started the following essay—longer than usual—while feeling dejected one day in mid-April. April 12. Not a great day. I still have some not great days, can feel overwhelmed by what used to be old hat.

To summarize my headspace, I’d say I live in constant fear that anything good will be lost. That I will continue to lose what matters to me until all that’s left is this TBI. Opportunities, abilities, my truck’s functionality. Those are just the easy ones. To use a word I’ve resisted calling myself, maybe this TBI has traumatized me. It did take a lot away; probably why I have such paranoia. Is it done? Will it take more? Can’t rule it out. When I’m asked “what’s wrong?” I reply “same as always” to avoid the can of worms.

Writing this, about those worms, feels embarrassing. It isn’t. A TBI is a real problem. One that doesn’t just go away. I’m my own worst enemy, have a habit of talking to myself: “Stop complaining. Do more. Suck it up. Really—you are still dealing with this?”

Yes. I am.

Aspects of “this” are lessening. Example, I am medically cleared to drive with an eyepatch. Because of the eyepatch, sometimes I put on the Pirates of the Caribbean soundtrack, “He’s a Pirate,” to create levity out of an undesirable situation.

I am easing into driving again. Was cleared exactly 15 months after the accident. The guy who cleared me guessed I was four years out. At this point, I’m acclimating to being back on the road. Drove to a meeting, drive myself to the gym. The days of only driving safe, easy roads to the same Osprey pole for practice are behind me. When I feel like this isn’t moving as fast as I’d like (it’s not), I remind myself of a physical therapist who thought I’d been recovering for 8-10 months when I hadn’t even been conscious for four, of the above mentioned driving instructor who thought I was years past where I am.

Other aspects are not lessening as much. The fine motor skills of my right hand still feel akin to those of a cowpie. I can’t run as well as I’d like—mechanics and stride-wise. My speech and voice are better than they were, but I feel less articulate. Before I say anything, I prepare myself. When should I stop to breathe? How should my mouth move? Go slowly. Emphasize the t sounds in “important.” When I’m alone, I have imaginary conversations. Ordering food is daunting. That’s part of why I love writing even more now. It doesn’t require I open my mouth.

Traumatic brain injury recovery isn’t known for brevity or ease—particularly with diffuse axonal injuries, the type I had. I’ll probably have some bad days for a while.

If reading about this isn’t what you were hoping for, I apologize. New writings on Rock & Hawk will often not be about traumatic brain injury—but it’s an important facet of my life. I acutely wish it wasn’t. Not writing about having sustained a TBI and working to come back from it would feel dishonest.

Here is the essay I started April 12. About TBI as “the invisible injury,” about dealing with bad days.

When certain thoughts rear their heads, when I’m feeling alone or desperate—bereft of autonomy and control, beholden to this TBI—I have a habit of searching for and listening to podcasts about brain injuries.

I’ve learned the hard way that Googling TBIs and going down the resultant rabbit holes will not make me feel less alone or desperate. It exacerbates those bad feelings. The internet will not provide the answers I’m looking for—if answers exist, which they rarely do. As much as I want to know the answer to “how long will a full TBI recovery take?” there’s no cut and dry one. It varies by injury, by person injured.

My recovery depends on me. The specifics of the injury that happened to me. My exercises, my diligence, my attitude. I can’t dictate how long recovery will take, but I can dictate my frame of mind. Can try my damnedest to encourage recovery along.

Recovery is different for everybody. If one is deemed capable of a full recovery—as I was, somehow, when still unconscious—it will take however long it takes. If I was giving positive recovery indications while comatose, they really must’ve been positive, which makes me hopeful. I wasn’t conscious so don’t remember. Probably seemingly insignificant signs. He reacted to this.

Googling TBIs after having one will convince you that certain problems, ones you maybe don’t have and haven’t indicated you will, are inevitabilities. This happens to me often. Podcasts and interviews, in my experience, are less dejecting than Google.

When scanning episode titles and descriptions, I seek anybody who understands what it is like to have an injury like this. The aim is to feel less isolated, find some stories that are relatable.

With this injury, I am the injured one, but I don’t have to go it alone—thank goodness. I have an amazing support system. When I get good news, I can share it. When I get bad news, I have people who will help sort it out. Still, it’s an issue that centers around me in the worst way. One that I alone receive the brunt of. If something goes wrong, it’s my brain.

For pastimes I love—fishing, getting outside, reading, writing—I have people to talk to about them or do them with. They don’t center just around me. The stakes are also lower. Worst case I don’t see a bird; a fish throws the hook; ideas prove elusive or challenging. This makes those activities more enjoyable. When something goes wrong, it never goes that wrong.

With the TBI, stakes are higher. Worst case can truly be worst case. When talking about the TBI I got, it can be difficult to convey what I want—not because I can’t find the words, but because it can feel like I’m speaking a different language.

Metaphors and similes help. With double vision, everything has a shadow. None of them are darker or different than what they’re shadows of. Sometimes you reach out to grab something and it just isn’t there. My knee used to resist bending as if there were tennis balls wedged behind it. Trying to open and close my right hand feels like what it is. The pathway between my brain and that hand is weakened. To get my right leg to comply when I run, it’s like trying to maneuver a peg leg—though it’s getting better. When I work up to decent weight on squats, my right knee shakes as if asking: What on earth is going on?

On some walks, I’ve noticed my “bad” leg feels more normal. Usually it is evident that my body wants to put its weight back on my “good” leg as soon as possible. For months I practiced walking to a metronome to address this. Recently I could walk, evenly, to the beat of some walking-paced songs.

TBIs are the kind of trial you have to experience to truly understand. In that sense, it’s good they’re not widely understood. The downside is, if you have one, it can feel as if you’re lacking people who get what you’re saying when you talk about it. The difficulty is the stark contrast. For anything else I do, there are people who understand.

For someone I love to fish with, there is my best fishing buddy. He has seen me catch almost every meaningful fish I’ve caught.

A specific brown trout comes to mind that took a Perdigon nymph on 7x tippet years ago. A trout that proved, between its mass and the current, too much for thin fluorocarbon and my glass four weight. I went back with my stouter five weight and 6x. They were picky, educated fish who saw plenty of flies, and I wanted to trick one. It took some time, but I did.

He also tied one of the most effective Clousers I’ve ever fished. I’ll never forget that fly, though have no idea what became of it. Must’ve lost it on a backcast against some rocks. There’s a specific beach we’ve fished together many times where that’s not unheard of.

For photographing deer, hoping to find bucks, shed hunting or going for hazelnut iced coffee, I have my hysterical, pizza-throwing, skilled photographer, screenwriting and albie-crazed friend.

Back when I was able to safely imbibe, we would have oceanside mojitos and take pictures of gulls dropping shellfish to break them open. I got some of my best Osprey photos with him. I took some more good ones after bringing my camera where he recommended.

We’ll get some great photos together again, sans mojitos—at least for me. He is more than welcome. I’ll sip on a LaCroix or a Spindrift.

Long story short, there are exceptional people in my life. Lots of them. Even when my life has been less than exceptional because of this TBI, they’ve been here. Some have cried with me or listened to me talk about the same problems again and again. Double vision, my hand, my right side, my speech, my stride. Others have been adamant that, given how I’m wired, I am not going to let this win. I hope they are right. I could go name by name and explain what makes each person special, but that’d be a lot of words.

For recovering from this brain injury—the way I fish or take pictures with those friends—there is, in a way, just me.

I am trying. They say that’s all you can do. Work hard to get better, jump through whatever hoops. It’s “just me,” but I have help for a lot of those hoops. Help without which I’d be unable to jump.

“It must be tough to be stuck in the middle,” I was recently told. I feel like I’m working very hard to not be in the middle. Have been told so. If I have a chance to do the work, I usually do it. If I’m standing around, I’ll stand just on my “bad” leg to work on balance. I walked over 10 miles and squeezed one of my grip strengtheners the whole time, because my grip strength was weakened. It was a blip on the charts, now I feel good about it. I remember repeating to myself as I walked and squeezed: This is fun for you. You love this. This is your new fun.

Even when it’s not weak (it’s possible my “bad” hand is now stronger than my “good” one), I will devote energy to grip strength. A good friend with historically weak grip has proclaimed every year for quite some time his “year of grip strength.” A year devoted to building it. This was my year of grip strength. Grip strength is an indicator of longevity, I’ve read. I want to be around for a bit.

Some comments from doctors have stuck with me. “You’re a clinical success.” “Your recovery has been insane.” I’ll work to keep being insane, in a good sense. I can remember back in physical therapy when I set the record for the longest distance they’d seen a patient walk for a timed walk test. The TBI has enjoyed over a year of control, but I control what I can.

“The middle” comment was in reference to my eyes, the uncertainty as to how my vision will be remedied. Which frankly is tough. Even when I feel good, looking at anything reminds me: “Yeah, but your eyes still aren’t working properly.”

My vision may get better on its own—though I am past the timeframe within which that typically happens. Vision therapy exercises are part of my daily routine, but with each passing day—as my eyes feel the same—I grow more skeptical. I’ve started guiltily/reluctantly treating surgery as a foregone conclusion. I’ve heard success stories and want one of my own. For surgery, they pop your eye out of the socket, cut the muscles that make it look straight ahead with the other, then reattach them so your eyes are in line—or at least closer. So I believe. That used to skeeve me out. It doesn’t anymore. Whatever works is what I want.

This TBI gave me fourth nerve palsy. Fourth nerve meaning my cranial fourth nerve. An eye muscle is paralyzed. Fourth nerve palsy, causing double vision, is not uncommon after head trauma. My eyes don’t line up. Instead of working together to create one image, I see two separate images—one from each eye.

When I’m alone, I look in the mirror to see if I can recognize the misalignment of my eyes. Some days it’s more evident. “Your left eye is out to lunch,” I say to myself. As apparent as it sometimes is to me, if you’re not looking for it you’d miss it.

To rectify this, I can wear an eyepatch. I wear one to drive. When I put on an eyepatch and don’t see double, sometimes I say to myself: “Holy shit! Remember seeing this way? How great this must’ve been!” I haven’t seen that way in quite some time.

People are often surprised the way for me to see one image is so straightforward. Patch an eye. It makes sense. If the eyes won’t work together, use one at a time. It seems like not a huge deal, but using just one eye is noticeably harder. I don’t want to wear an eyepatch forever—already do as infrequently as I can. For a time, I would tell myself, “but James Joyce wore one!” (Not for fourth nerve palsy.) James Joyce is great, but it’s still preferable to not wear an eyepatch. You don’t realize how great it is to use two eyes until you have to rely on just one.

When I talk about this injury, it can be arduous to explain, difficult to feel understood. Some have been along for for the entire ride and don’t need explanations. They are all too aware of persistent sadnesses peculiar to me, well-versed in this ordeal. I am more grateful than they know, would not be coming back as I am had I been facing this alone.

As far as persistent sadnesses, take fishing. What once made me happy can make me quite sad. I used to spend hours tying saltwater streamers, fished with them most nights—then lost that capability. I’m working to get it back. I will get it back. Mark my words. “He will do everything he used to,” a neurologist asserted when I was still comatose. Let’s prove them right.

Sooner than I might think—let’s pray—I’ll feel a striper’s weight bending my fly rod to the cork after it takes a Lefty’s Deceiver I tied. After a good fight I’ll land it, unhook it, wading in the Atlantic. Hold it in the water until it bites down on my thumb and swims off. Saltwater fly fishing consumed me for years. I had to forget that I was once good at it. By no fault of my own I lost my ability, now must fight to get it back. A sadness peculiar to me.

I crave stories of survivors. Though I chafe at calling myself a survivor, I am. I survived. One who survives is a survivor.

Having survived a TBI, I recognize that if I want to feel resonance or relatability, survivor stories are where I ought to look. I also crave motivation, hope. Evidence that this does get better and won’t stay this way forever.

One podcast I found in the midst of some loneliness and desperation was an episode of The TBI Therapist Podcast. Survivor story: From TBI coma to marathon runner with Erica Baggett.

Baggett was in an automotive accident. She was ejected from her vehicle into the median after being hit by an 18-wheeler—the same type of vehicle that hit us. She was then in a coma, as I also was.

She talks about an increase in anxiety, intrusive thoughts. My anxiety has increased. It already wasn’t negligible. My paranoia too. I am far less trusting of quite literally anything, never believe it won’t go awry until it is completely settled and finished with. My hypothesis is because this happened on a birding trip that was supposed to be fun—a trip that became this—I see almost anything as something that can become this. This being any unintended horrible consequences. I also have intrusive thoughts. Predominantly worries I never had so aggressively before.

Baggett had difficulty sleeping too, which is why she started running. I still have difficulty sleeping, spend nighttime hours tossing and turning or just laying there, taking painful inventory of my intrusive worries. Melatonin doesn’t help, makes me miss the days I was prescribed trazadone—though I’d take my pill and be barely able to get to bed.

Here are some other examples that hit home:

“Most people thought, oh my gosh, so lucky you lived…while I’m thinking, ‘I’m alive but I’m not living.’”

That’s how I feel—like I’ve been merely existing. Breathing. Taking up space.

A promising event recently happened. Afterward I was asked, “How do you feel?” My answer was long, but included “less like a leech” and “more valuable.” So, for the past year and change I’ve felt like a leech with no value. Alive but not living.

Living, to me, is driving myself to a beach or a salt pond after a day of worthwhile work, wading out by headlamp to catch fish on the fly, driving triumphantly home. Living is being able to read a hefty tome without having to turn my head uncomfortably to combat double vision.

Quick aside. I’ve been a reader my whole life; can correlate parts of my life with the significant books I’d been reading.

Before I moved to New York, Kent Russell’s I Am Sorry To Think I Have Raised a Timid Son. Then lots of standout books for graduate school. Some still make me smile as I recollect how they made me think. Suzy Hansen’s Notes on a Foreign Country, Vivian Gornick’s The Situation and The Story, Janet Malcom’s The Journalist and the Murderer.

Then I came to realize New York was not for me. Physically there, but mentally in Kamchatka or Seychelles, I read Izaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler. My copy is heavily dog-eared and tabbed. When I left New York, Jim Harrison’s Wolf: A False Memoir. Unexpectedly happy working a job I almost didn’t take, unsure what was next, Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. I craved spending time with Konstantin Levin, rightly or wrongly saw him as a kindred spirit. When I at least started the process of elimination regarding what might be next: Russell Banks’ Affliction, Wendell Berry’s The Art of Loading Brush.

With the city in my rearview, I knew I wanted a life with certain concerns—ones I always had but wanted to focus more on. Birds, fish, what I write about here. I reread Gessner’s Return of the Osprey and read Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk.

When I had my first truly serious angling year and wanted a fishing life, my sacred text was Tom McGuane’s The Longest Silence—which I still often revisit. I’d been down a McGuane rabbit hole. The Sporting Club, Ninety-two in the Shade, Crow Fair, Panama, Gallatin Canyon—punctuated by forays into Gierach’s Trout Bum, A Fly Rod of Your Own, and All Fishermen are Liars.

Then so much went wrong. When I was sent home from the hospital after a TBI and wanted to try to read again, my father gave me Gretel Ehrlich’s A Match to the Heart. With my own long recovery road about to begin, I read about how she recovered from being struck by lightning. The only books I felt comfortable reading, visually, after that were Gene Lodgson’s Letter To A Young Farmer and Robert Thorson’s Stone by Stone. To train my speech, I read aloud.

That was a long-winded and probably unnecessary digression to establish that reading means a lot to me. Now reading seems less desirable, feels like a chore. Not because I don’t like it, it just presents other challenges than reading. There are books I don’t want to wait any longer to start. Chris Dombrowski’s Body of Water, Suzanne Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree. Now is as good a time as any for me to finally finish Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass. I’ve got John McPhee galore, a Louise Erdrich that’s been sitting there, a lineup of Jim Harrison.

I still try to read, but wouldn’t say I read in the same way. I do it because I know I would have been doing it had this not happened—plus I have many books. Retaining information isn’t the obstacle. The hard part is seeing the words.

Until I can read more easily, am out there under the stars fishing, I’m not living.

Baggett also says, “In the back of my head, while I’m running, I’m thinking—you know—a year ago, two years ago, I was in a coma. And now I’m running ten miles, and then I kept going.”

I’ve had a similar line of thinking. I did start running in 2022, though my stride is still iffy and I’m slow. Maxed out at a 10k in February this year, but now have been more eagerly pursuing the weights. Meathead habits die hard—especially after over a decade in the weight room. I’ve spent a lot of time in squat racks.

Still, running is good for you. I see this juncture as the opening of a new chapter, so maybe I’ll run more. Nothing crazy. When I managed to run a 5k race seven months out from the accident and coma, I felt triumph.

Weights-wise, I never used to boast about leg press—but it’s a safe way to supplement squats, which are harder now, so I do it. Eclipsed 500 pounds. Felt damn good about it. Felt the same when I finally broke 200 pounds on squats again. I’m tempted to add a caveat about how much I used to squat, but I’m working to not constantly compare myself to how I was.

Another quote I found resonant was when Baggett said, “Because of my traumatic—or because of the traumatic brain injury that I sustained. Not ‘mine’ because it does not own me.”

The same inner debacle about what to call it is one I’ve had. My traumatic brain injury? The traumatic brain injury?

“My” connotes ownership. Though I am working to quell my denial—which Baggett also grappled with—and to own that this happened, I do not want to speak in a way about this TBI that gives it more power than it already has.

When I think of words I precede with my, they feel different than traumatic brain injury. My truck; my family; my friends; my fly rods; my rowboat; my camera; my books. My gets used with what I love. My TBI? No, no, no—one of these is not like the others. The traumatic brain injury I sustained. Demote it.

As a writer, the traumatic brain injury I sustained feels wordy, less precise than the more direct: my TBI. Given factors other than verbosity and directness, it seems a worthwhile exception to the rules.

This brain injury happened to me. The injured brain lives in my skull. But if I can avoid calling this TBI my brain injury, I’ll call it something else. A puny act of protest. A futile one, but it feels good. And I want to feel good.

Baggett also said: “I looked okay but I didn’t feel okay.”

I look fine. When I met somebody new who heard what happened, they said they’d have no idea if they didn’t already know. I look pretty much how I did—maybe more grey, skinnier—but feel suboptimal in lingering ways. I’m still coping with some symptoms, won’t enumerate them. I know I am the same guy, but can’t do the same actions the same way yet.

Key word: Yet. I will work until yet is now, however long that takes. This TBI has proven to be quite a lot, but it is undeniably a source of motivation—something I can act in spite of. Anger can be unproductive, but being angry at this brain injury for changing my life how it did is a reliable source of motivation.

It motivates me to dig postholes, to do more weight in the gym. Gets me out the door to try running, gives me a reason. I will never be who I was, will always be a person who sustained a TBI—but I can try my absolute best to do what I would have, even if it takes years to get good again.

So, I am afflicted with the invisible injury. If I broke my arm, I’d wear a cast. It’d be clear what I wouldn’t be able to do. You don’t see a guy in a cast and ask him to do chin-ups.

A brain injury is different. It doesn’t result in a cast. Nobody knows what I can or can’t do—so if there’s something I’d rather not be asked to do, it’s not clear just by looking at me. I look able to do pretty much whatever. I’m proud of what I’ve become able to do again. I’ve learned to work around the obstacles this injury presents.

Contrarily, I am frustrated by what I can’t do yet, would hate if you asked me to do something I always did that’s newly difficult. Would hate being unable to deliver. Because you can’t tell what I can or can’t do by looking at me, it’s up to me to be transparent about my limitations.

This is where being as stubborn as I am doesn’t help. If I don’t admit something is different, I convince myself it isn’t. Limitations only exist if I acknowledge them, I can still do what I want to, I tell myself. I love challenging tasks—fly fishing, birding, fly tying, reading, etc.—so when something proves challenging, my reaction is, No shit. This would be hard without a TBI. But it might be challenging in new ways related to neurological pathways.

The idea of “my limitations” makes me productively furious. I don’t want limitations. There are some I’ve already worked past. Limitations: It’s up to me to work to eradicate them.

I have no hugely apparent physical scars to point to—which just emphasizes how lucky I am. My luck is regularly emphasized and re-emphasized. I broke no bones after being hit by an 18-wheeler, no memory problems, haven’t had seizures, have had no surgeries (though might need eye surgery).

This prompts my denial—which isn’t as gone as I sometimes believe. Did I really even have a TBI? For months I convinced myself no, but the answer is yes. Lots of people have physical trauma along with brain trauma when they endure an event that results in a TBI. My scars, on the other hand, are easy to miss.

There’s a small one where my trach went into my throat, between my collarbones. It’s only been recognized and commented on once or twice. There’s another where my feeding tube went into my belly—only apparent if I take off my shirt. There’s one more where something, I forget what it was called, went into my arm. Even I don’t notice that one, forget which arm it’s on and where. Couldn’t point it out if you asked.

The goal is not to notice my—to use the dreaded word again—limitations. That’s sort of what this Substack is becoming about. I’ll always write about birds, about fishing. Now I have a new starting point to write from. The work I’ll do to eradicate some of my limitations, to make sure nothing keeps me from fishing or birding, to lessen what I can’t nullify yet.

TBIs are an invisible injury. I don’t look like I have limitations. The goal is to work to arrive at a point where I don’t.

I can only imagine how difficult it is to put the TBI experience into words- but I am grateful to you that you are doing it. None of us who love you will ever truly understand, as much as we want to understand. We are just grateful to still have you. Keep writing! Love you!