Unpacking My Library

On collection, Walter Benjamin, Geoff Dyer, Thomas Bernhard, Fredrick Sjöberg, and others.

I started this in 2016. My life and library have changed since then, the latter has grown, shrunk, been moved and rearranged. I’ve donated hundreds of books, probably a thousand. Let’s not pretend I haven’t also obtained more.

“I am unpacking my library. Yes, I am.”

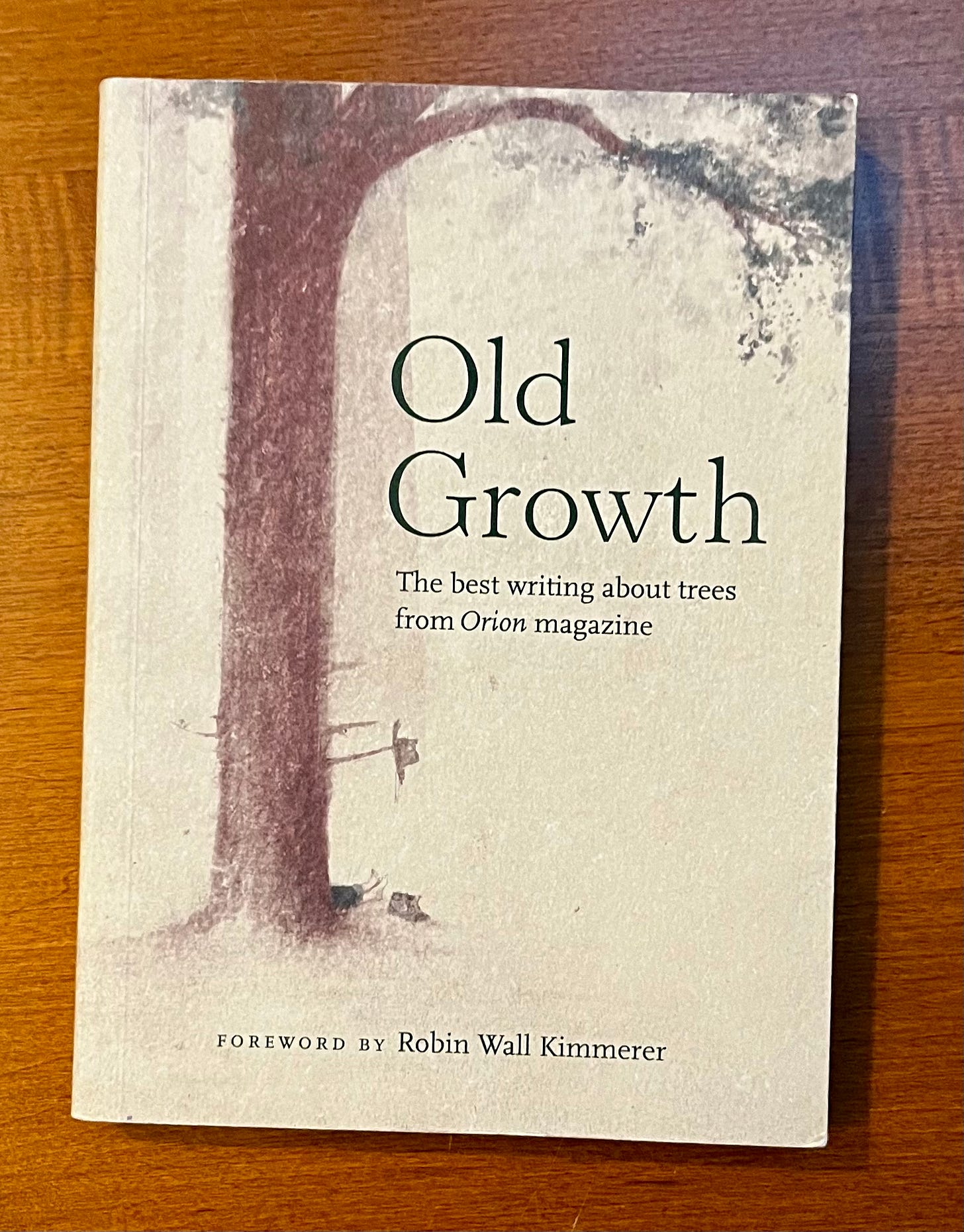

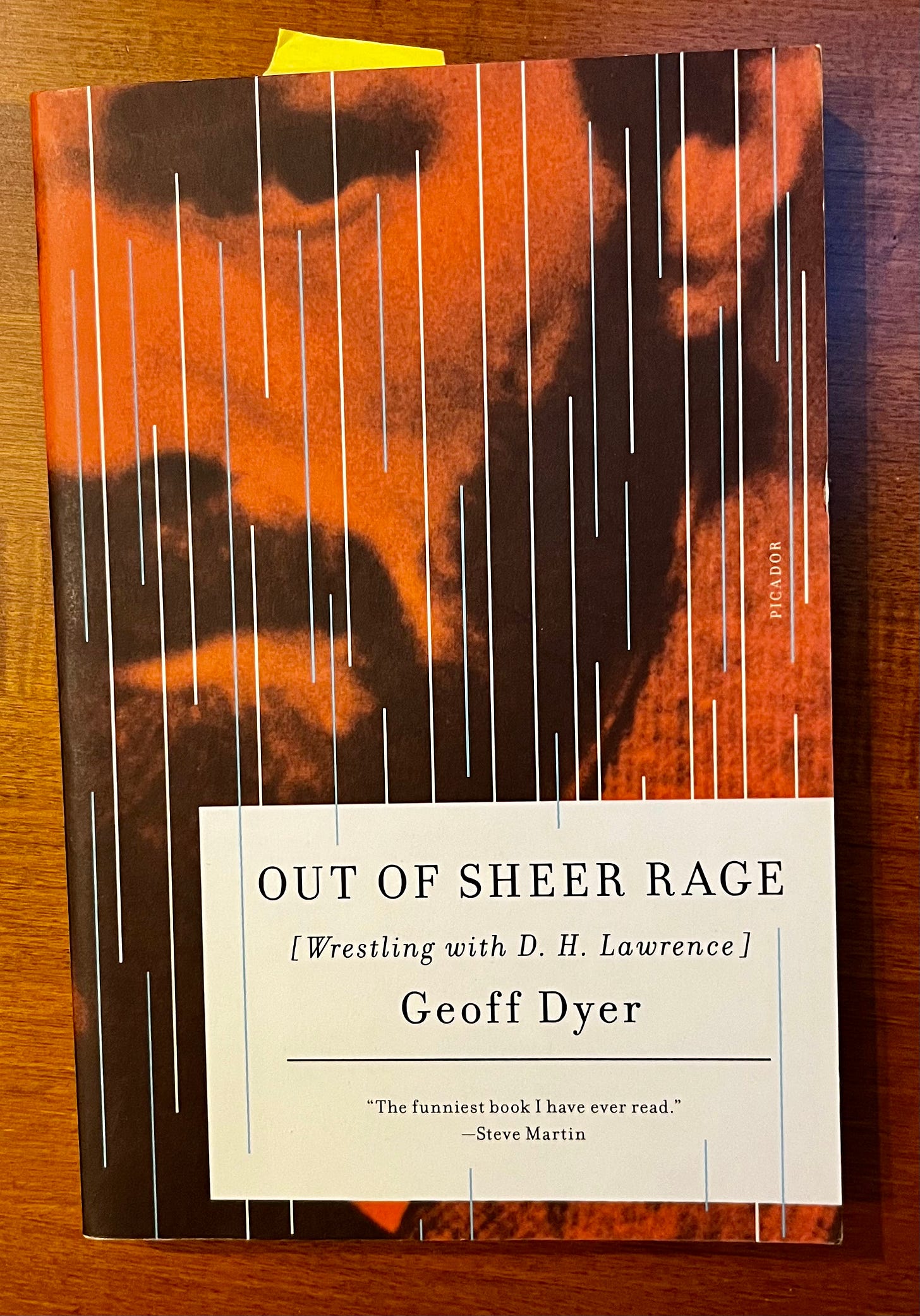

So begins Walter Benjamin’s essay on book collecting, “Unpacking My Library”—and Geoff Dyer’s of the same title in Otherwise Known as the Human Condition.

Unpacking a library does not lend itself to a tidy resolution. Unpacking and arranging a library is, Dyer writes, “a source of unresolvable pleasure.” Also: torment.

Benjamin notes “there is in the life of a collector a dialectical tension between the poles of order and disorder.” I crave order, but the form it takes is often disorderly and comprehensible only to me.

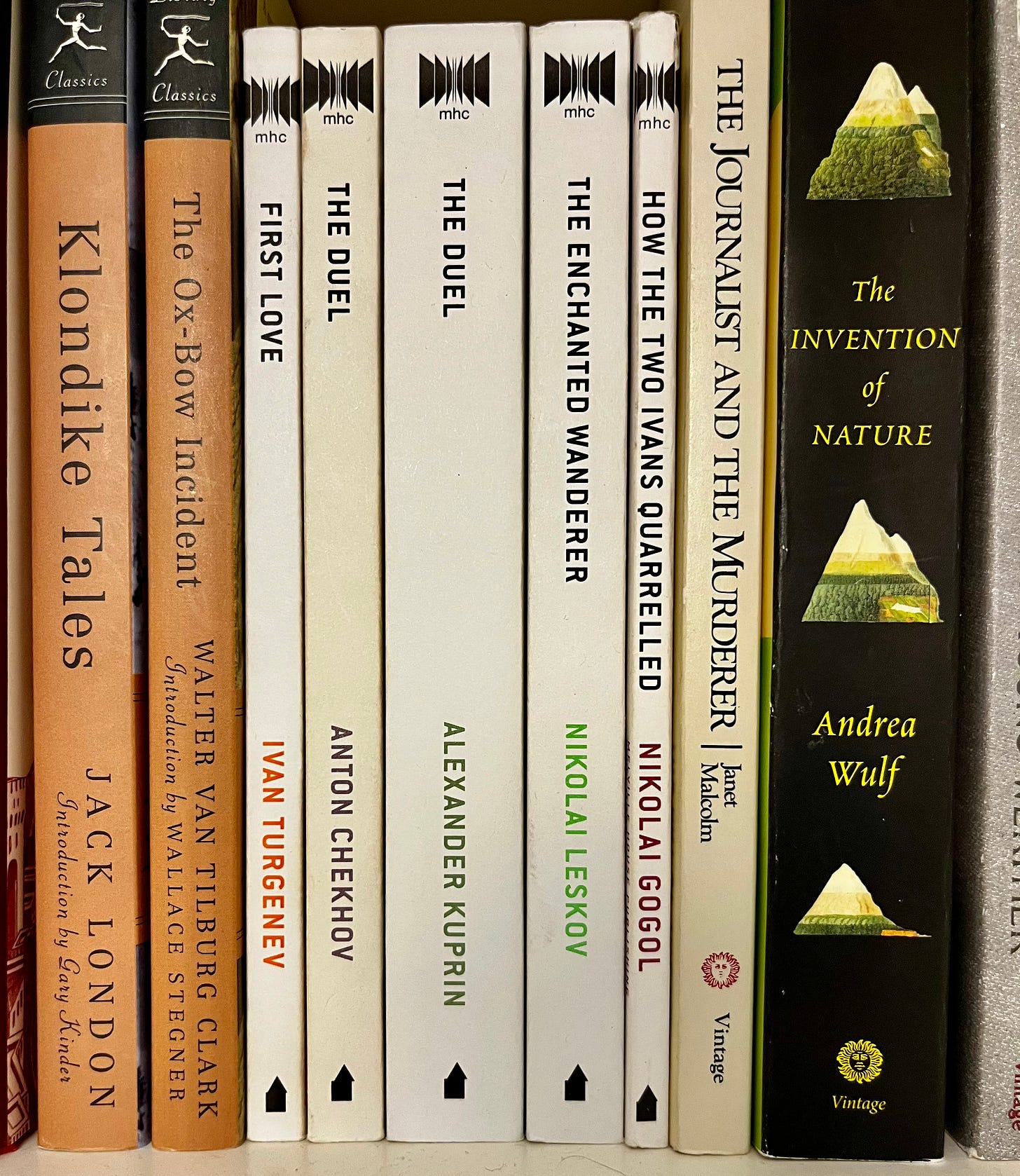

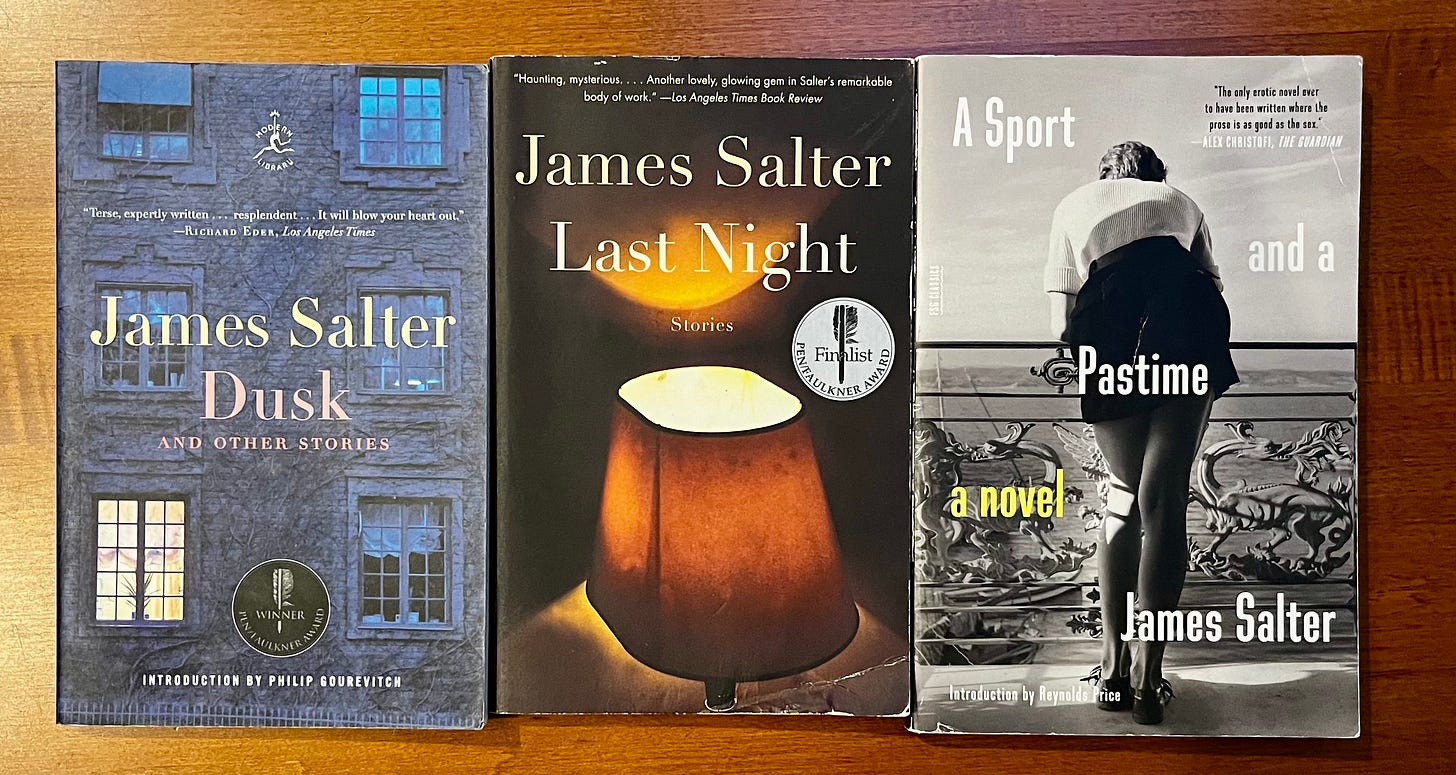

Friendly authors brush shoulders.1 Other shelving decisions are more practical.

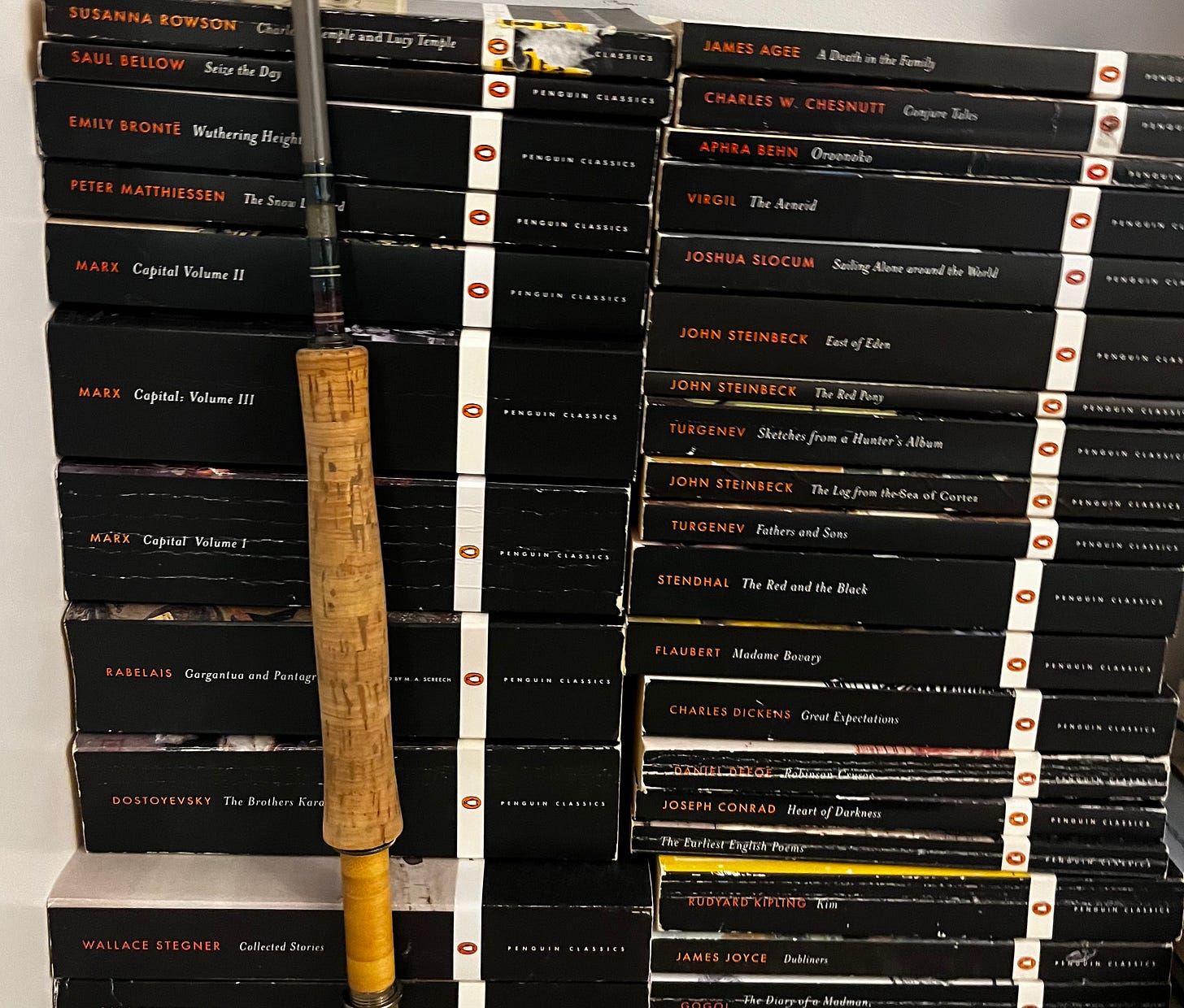

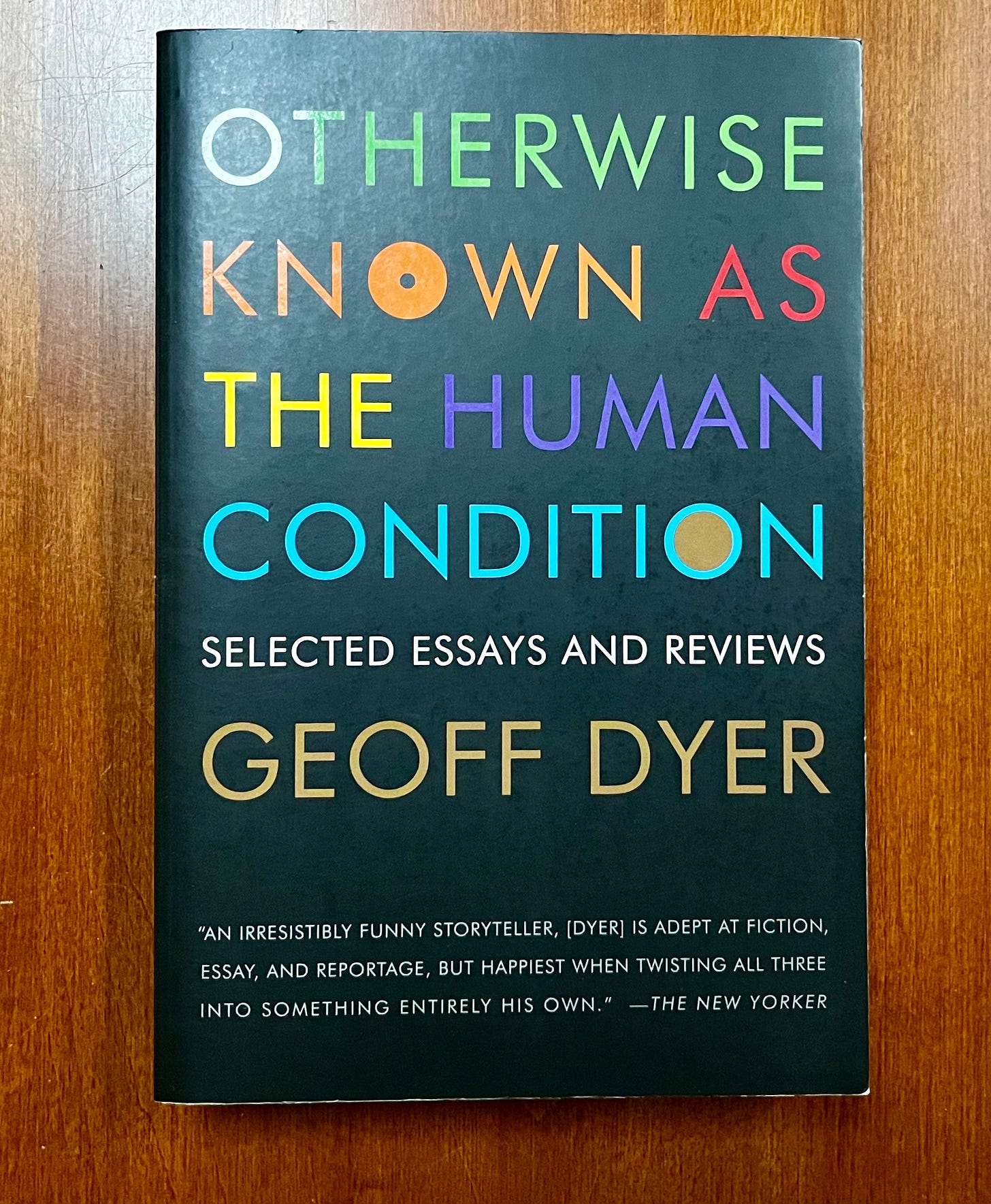

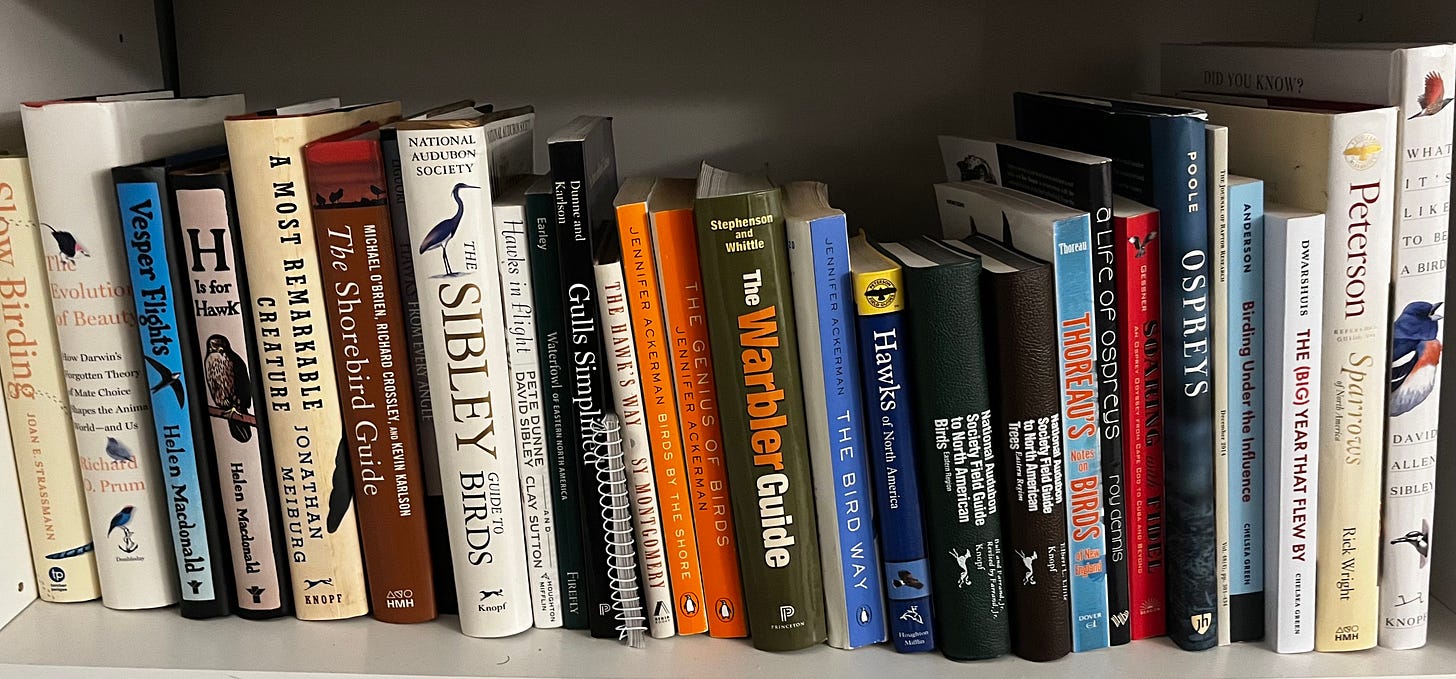

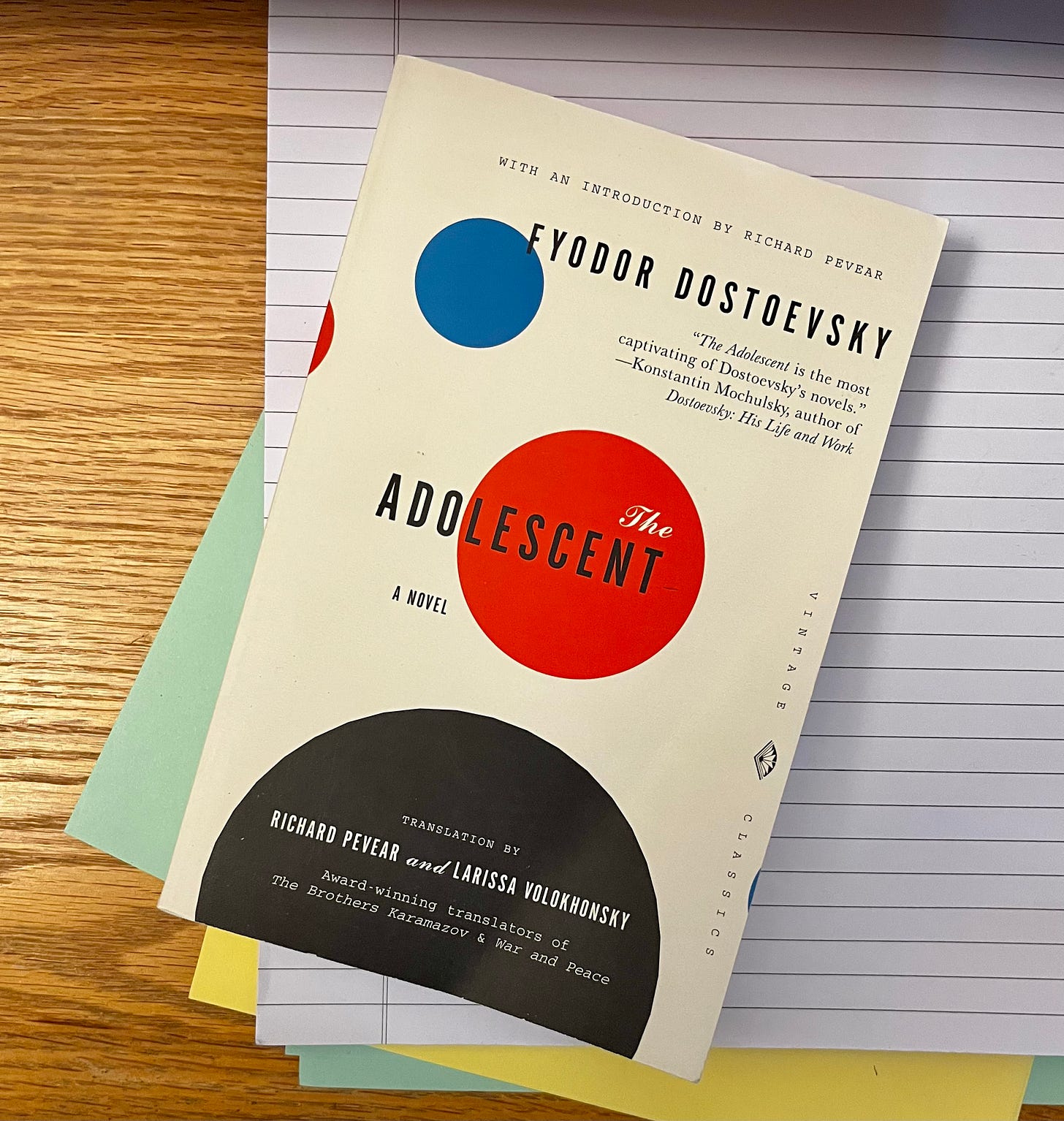

I want Penguin Classics lined up alphabetically, Dostoevsky Vintage Classics arranged by thickness, NYRB classics next to each other wherever they fit—J.A. Baker’s The Peregrine is with other bird books.

Vintage Classics go neatly alongside each other like rows of so many teeth.

A challenge of arranging books as part of a larger “scene,” to quote Benjamin, is that reading books—their raison d'être—requires removing them from the shelf.

This makes for disorder—a hole in Dostoevsky, a missing tooth in the Vintage Classics smile. Disorder is endemic to a working library. If too orderly, it is in disuse.

I began assembling my library when I worked at a small, independent bookstore. I’ve worked at two. At the second I got an employee discount and would crouch in front of different sections, thumbing through books before committing to a purchase.

I also met a generous benefactor, an older coworker with thousands of books. He wanted to get rid of many; I was happy to take some. He’d bring bags of them and talk about authors,2 explaining their strengths and weaknesses as if bequeathing precious truths.

He felt like an elder guide I was meant to encounter—our paths preordained to cross. Then I moved to New York. Before leaving, I gave him The Big Rock Candy Mountain. He liked Stegner; The Big Rock Candy Mountain is my favorite Stegner. He didn’t have a copy.

By that time I’d amassed a library. It has warranted U-Haul trips entirely of books.

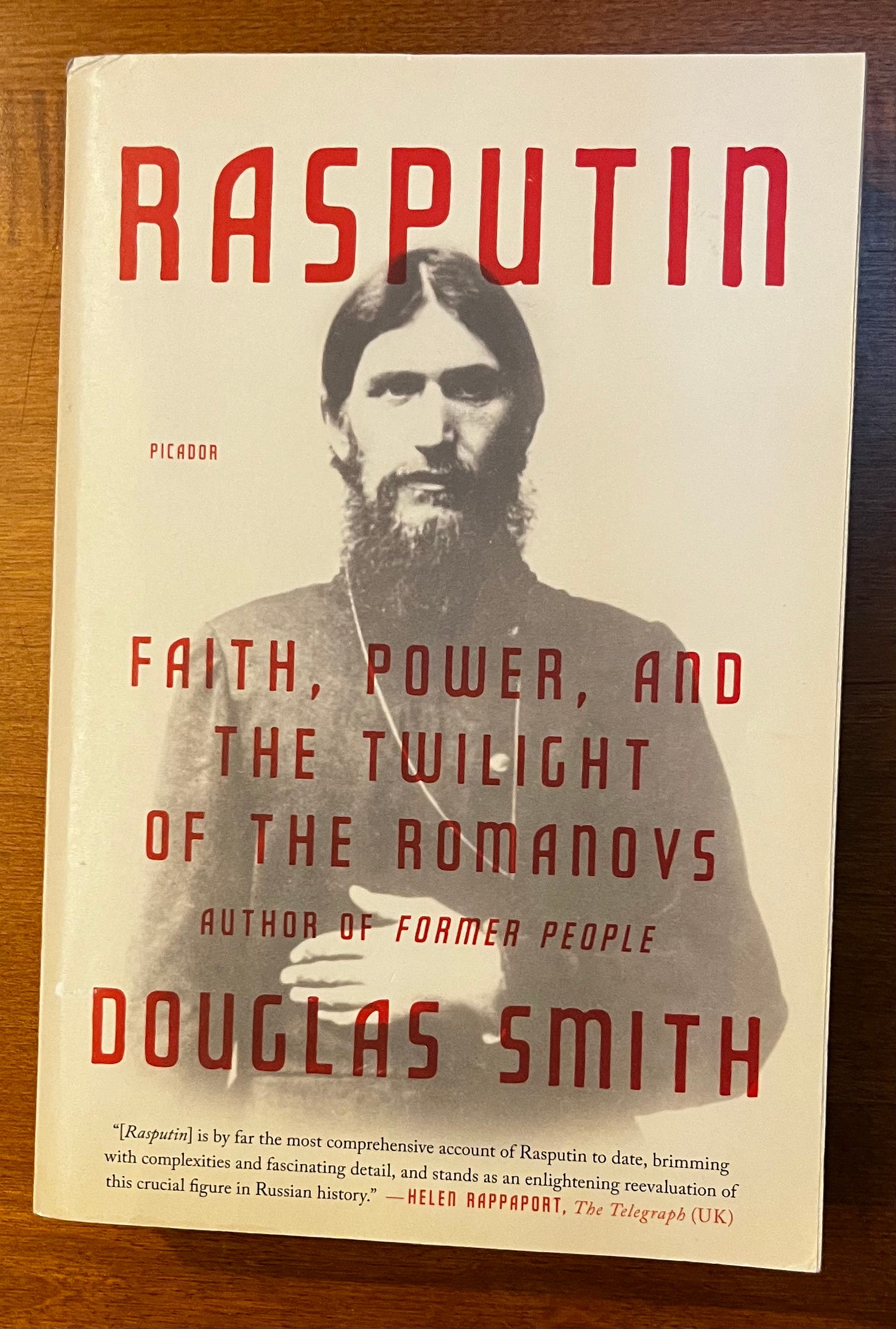

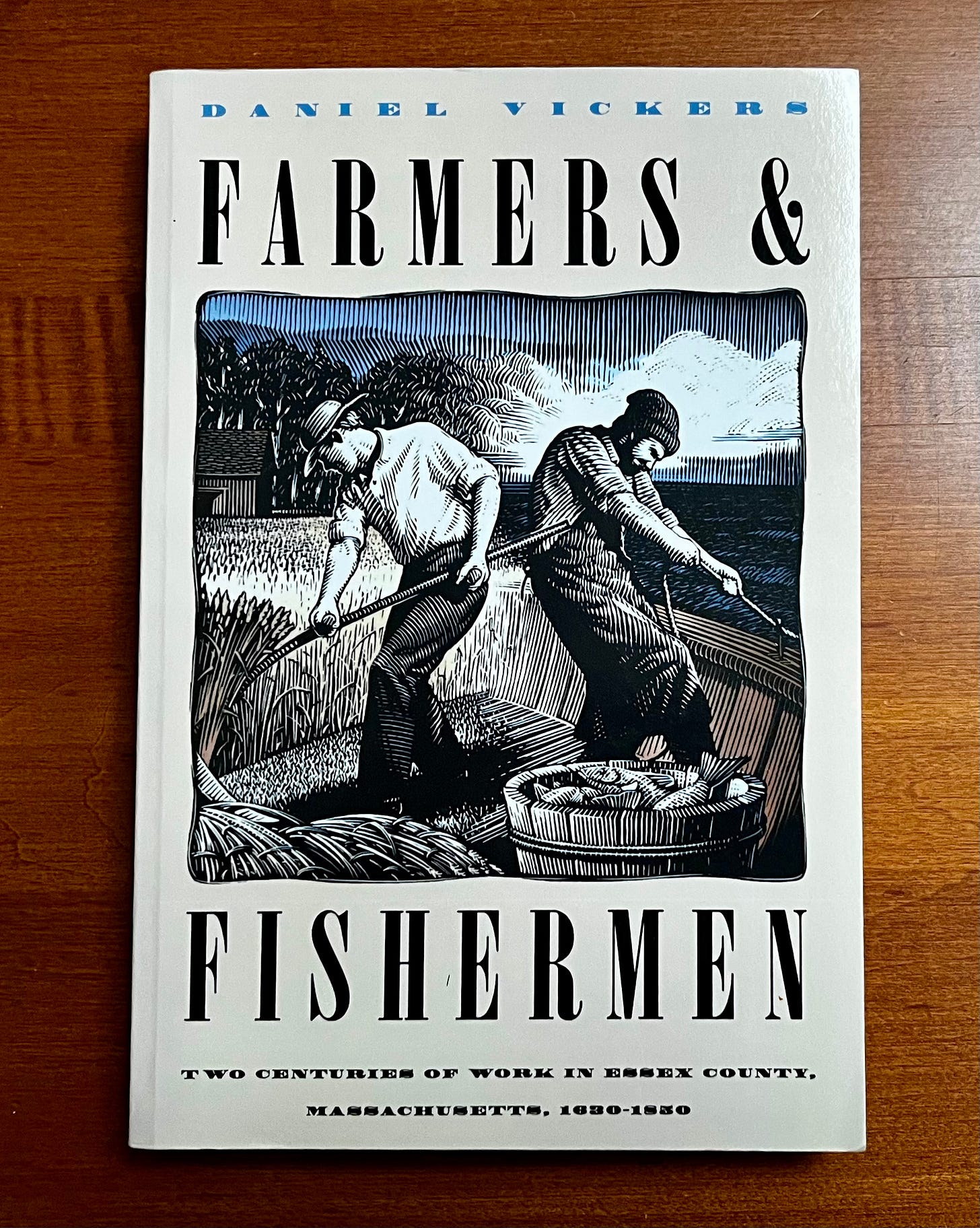

I’ve tried to avoid acquiring too many books by donating or giving them away. Some I gave to my friend whose home had built-in bookshelves to fill; I gave more to another, including Bootleggers, Lobstermen & Lumberjacks which I regret parting with. I almost gave him Matthiessen’s Men’s Lives and Vickers’ Farmers and Fishermen: Two Centuries of Work in Essex County, Massachusetts, 1630–1850. I’m glad I didn’t.

There are moments I frustratedly curse how much space my books require, but it is nice to see obsessions I’ve had—subjects, writers, etc.—represented in books.

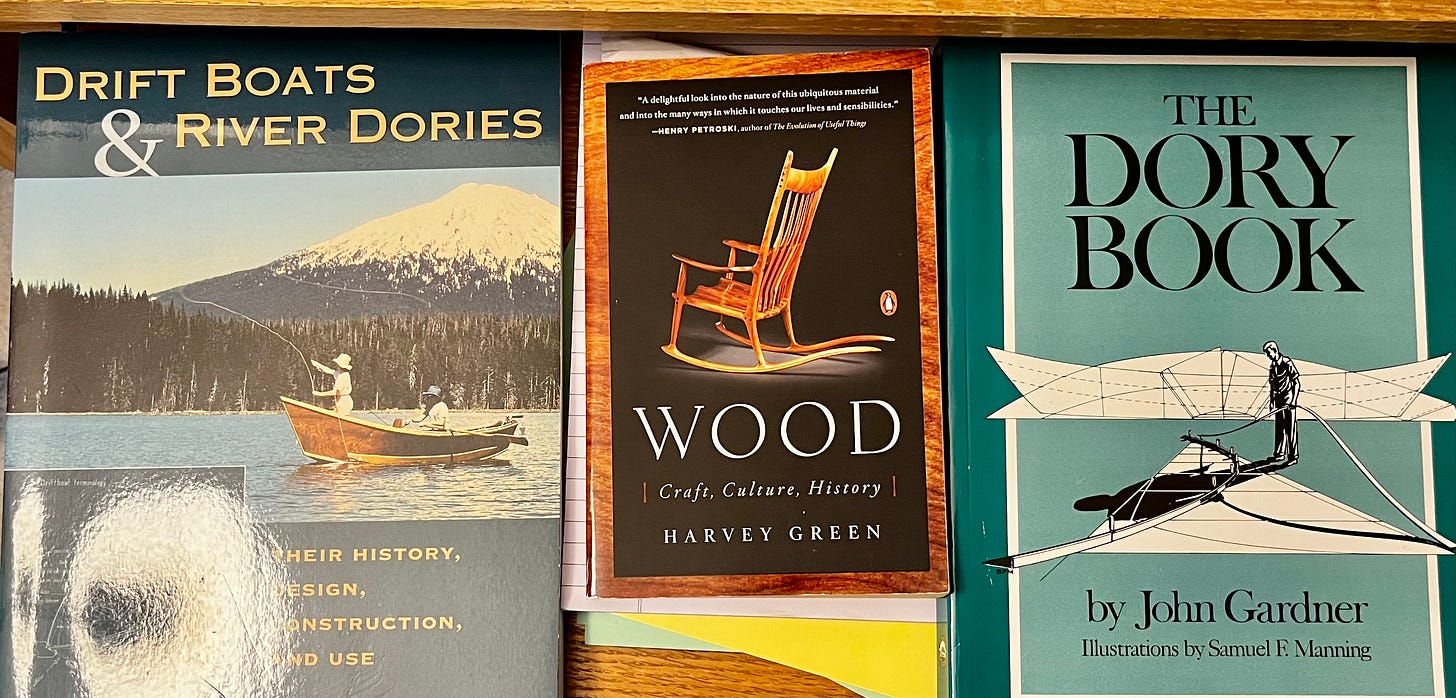

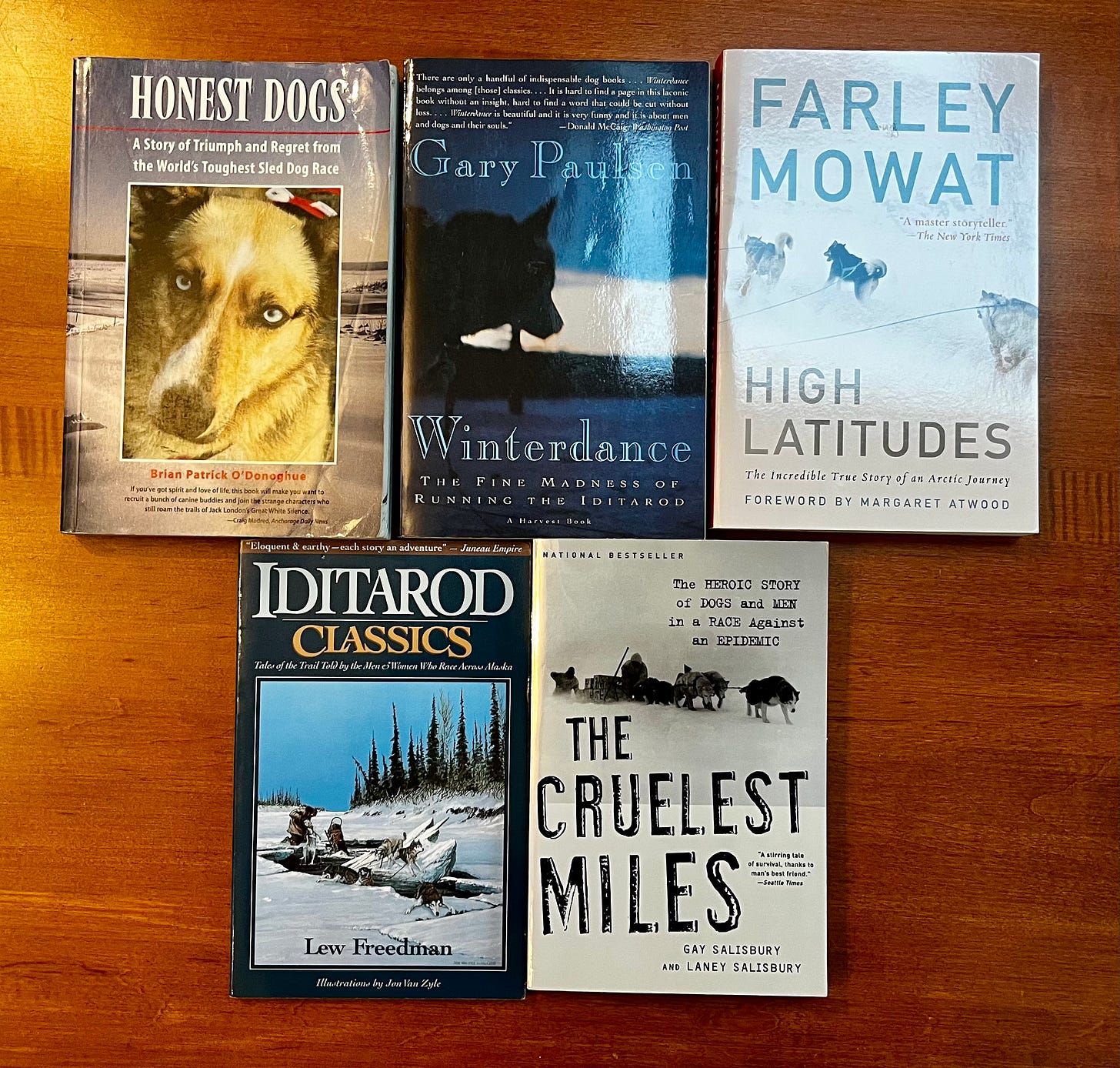

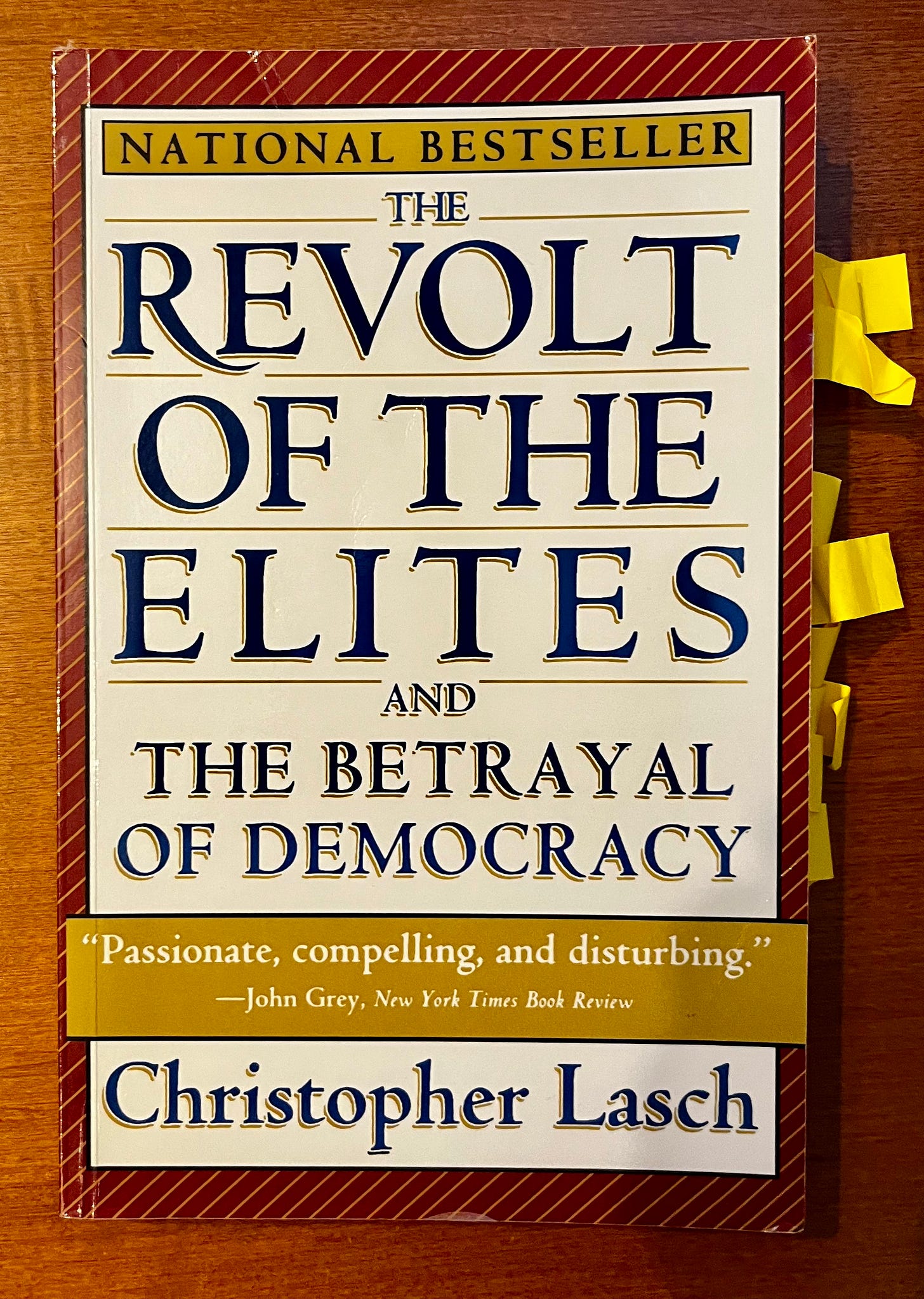

Wooden boats,3 Christopher Lasch, raptors in flight, Anaïs Nin, sled dogs, anarcho-primitivism.

Of course, birds.

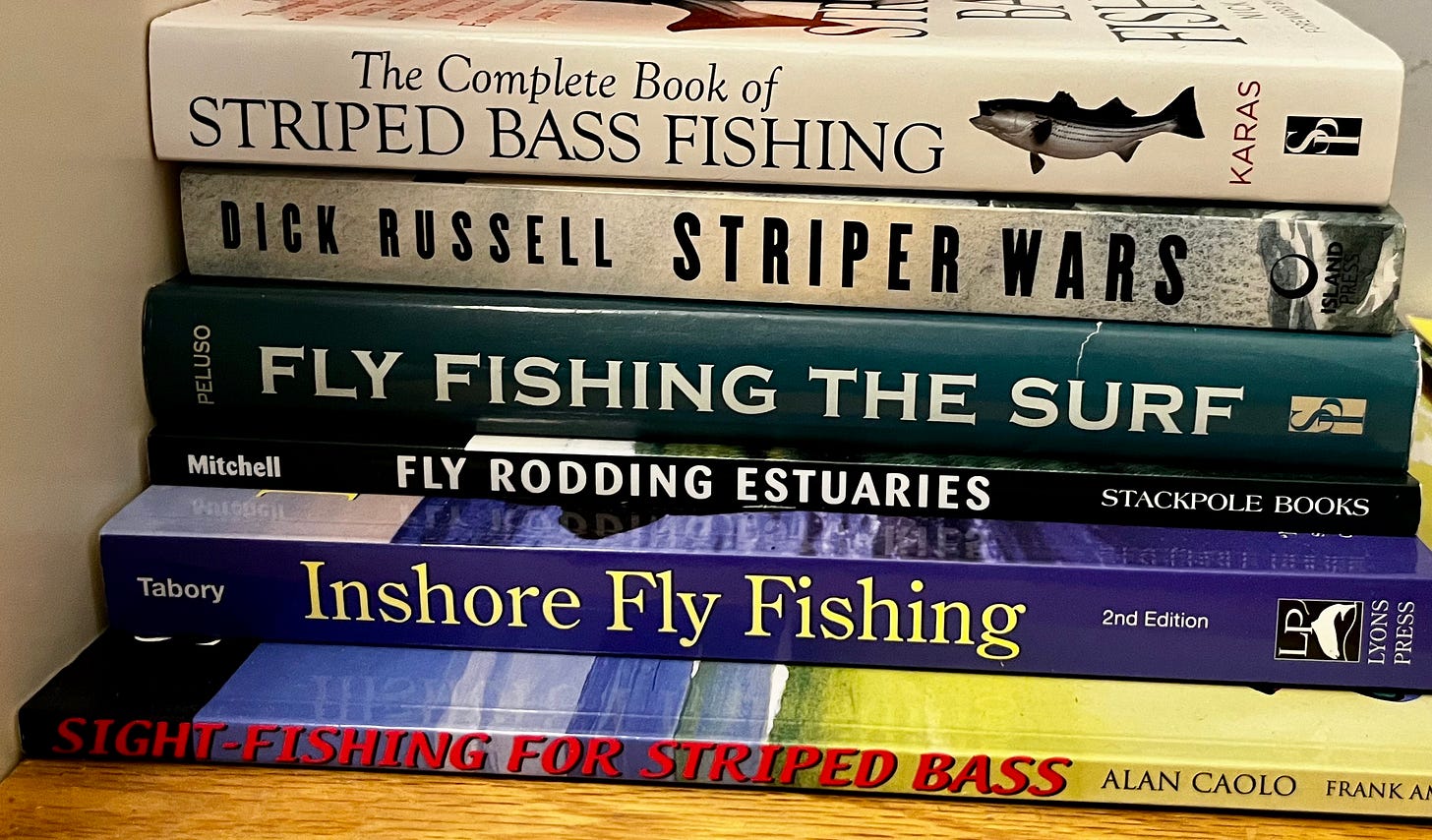

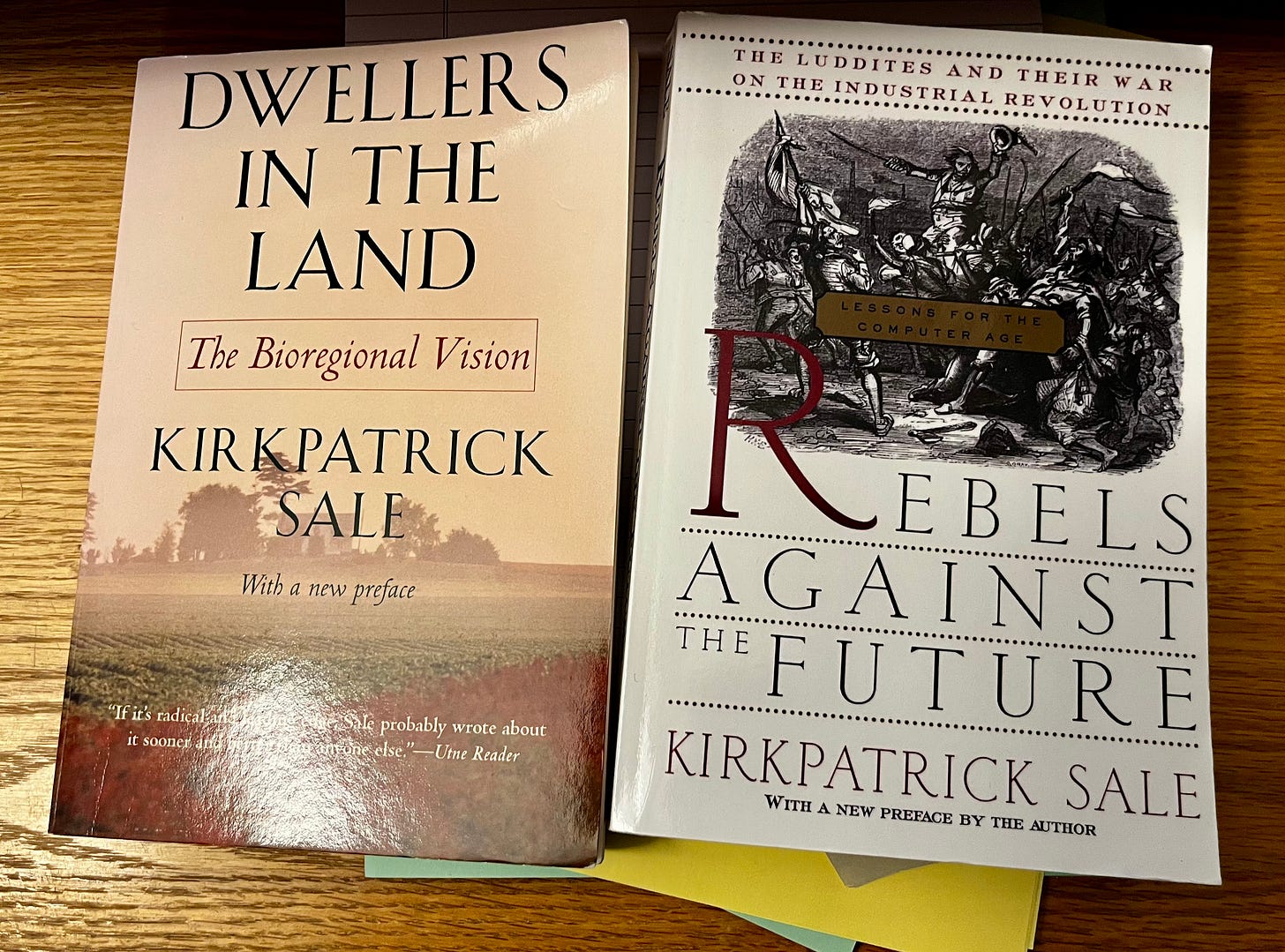

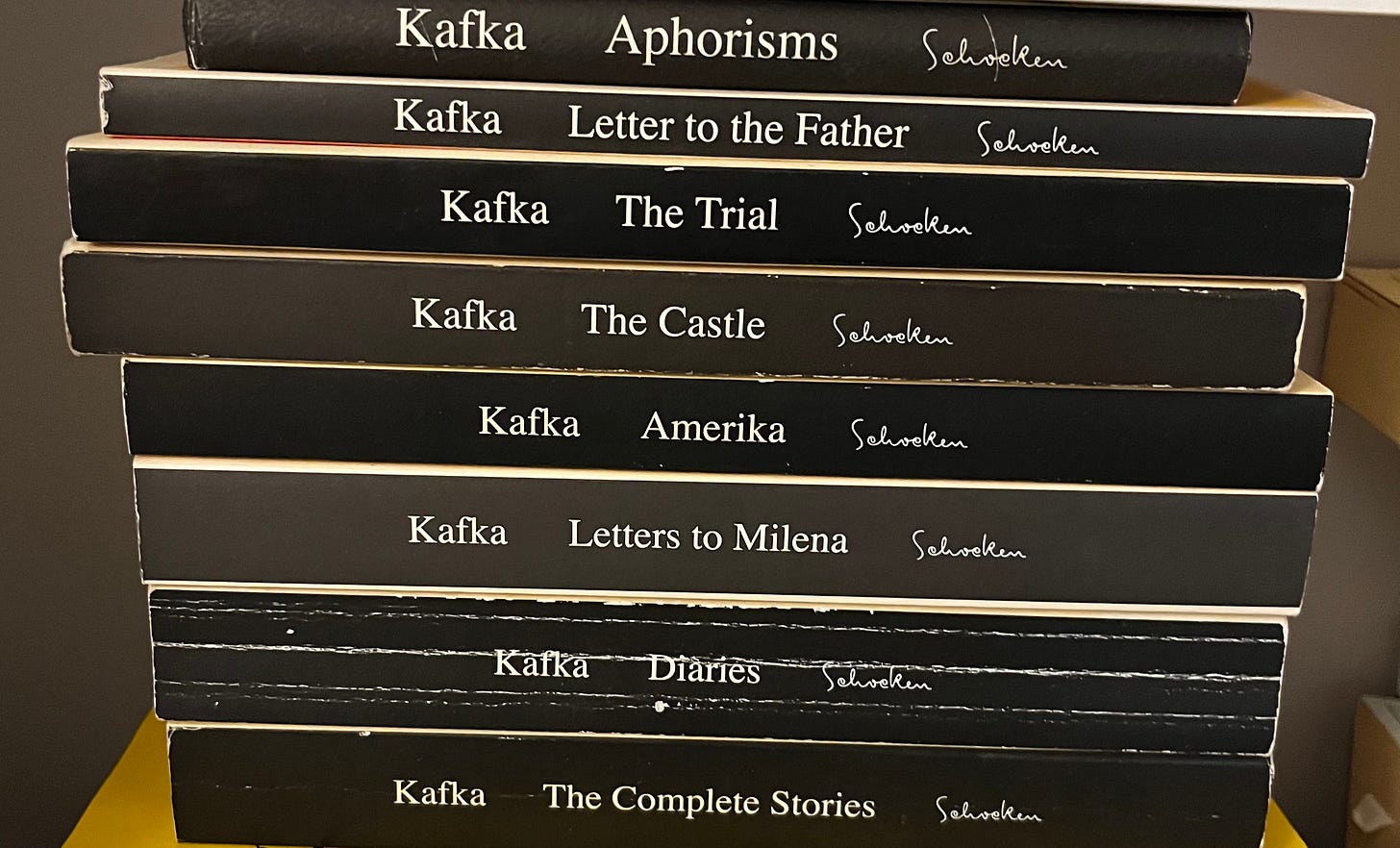

Kirkpatrick Sale, stripers, Kafka, brook trout, Melville House novellas.

The list is long. Interests still, no longer obsessions.

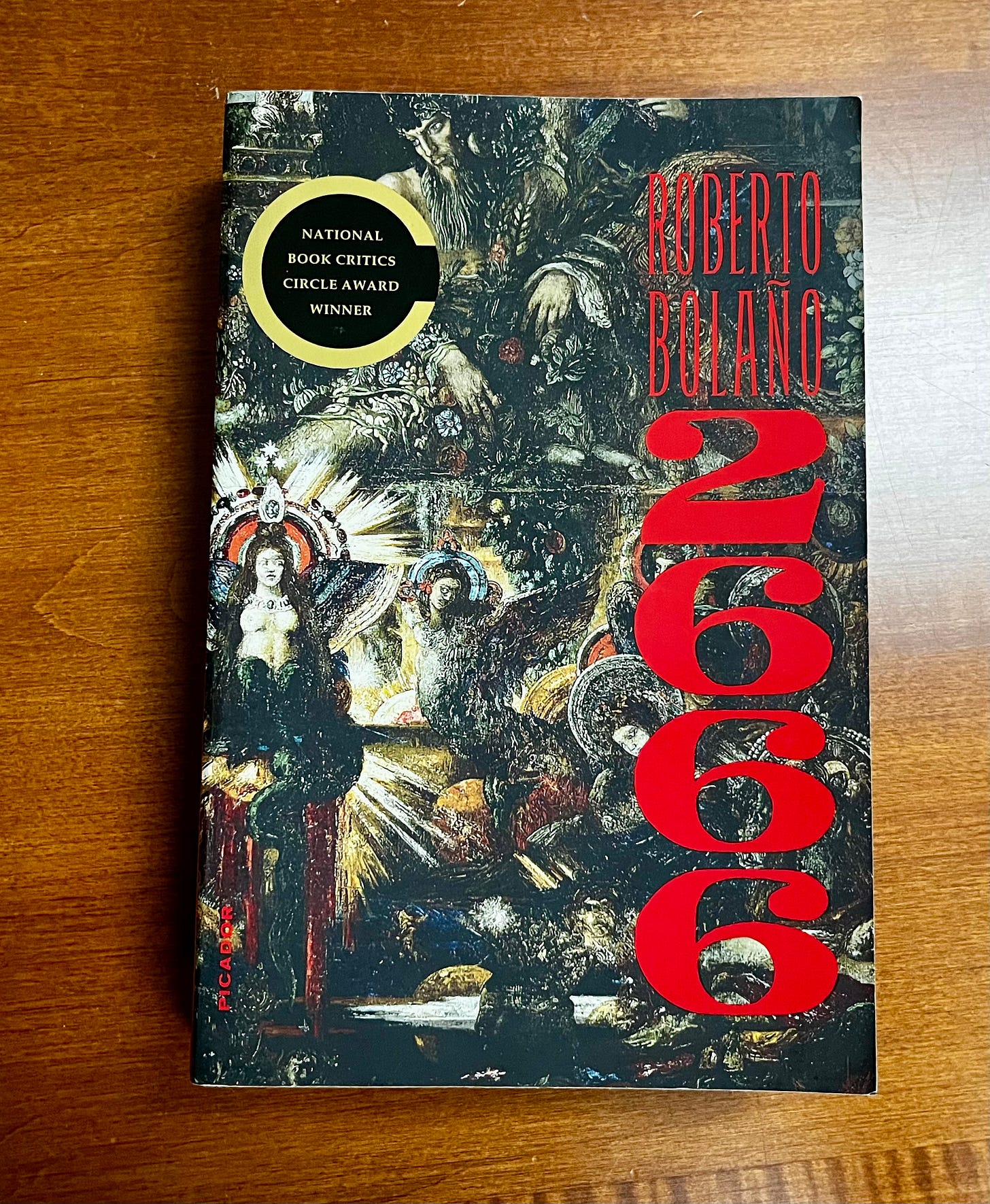

I don’t mind rearranging or going through my books to thin the library. It allows me to hold, start, and/or finish some—to be lovingly tormented by questions: Do I really want Bolaño’s 2666, which consumed a month of my life, relegated to a bottom shelf?

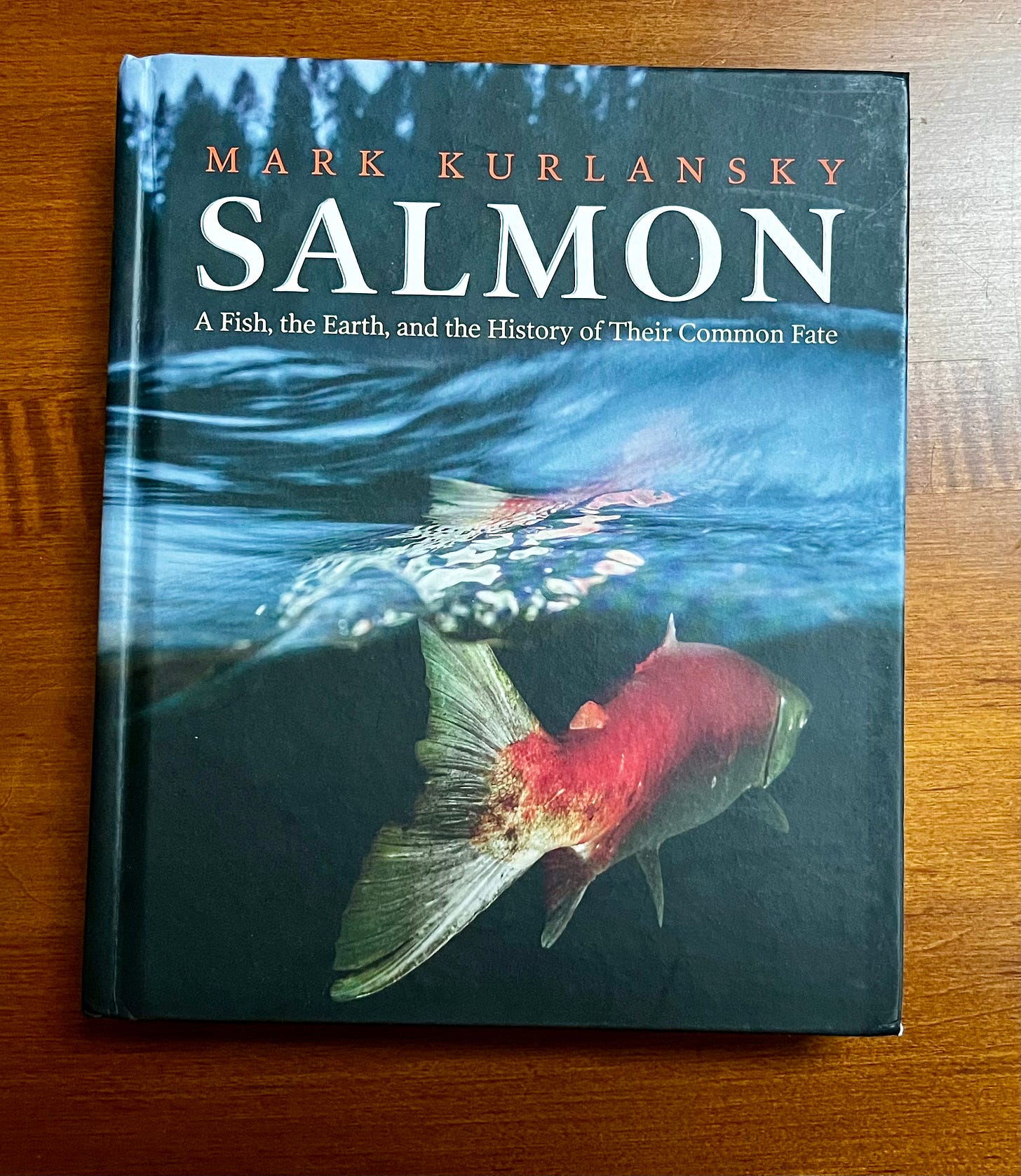

There are also spacial issues. David Foster’s A Meeting of Land and Sea: Nature and the Future of Martha's Vineyard doesn’t fit properly anywhere. Mark Kurlansky’s Salmon is beautiful but too square. The spine juts out when it’s next to books of similar height.

What about books I want to read or reread? I’d have to remove them from the shelf, leaving a gap. Until I’m ready to accept a gap in my “scene,” a book remains shelved in the realm of “order.”

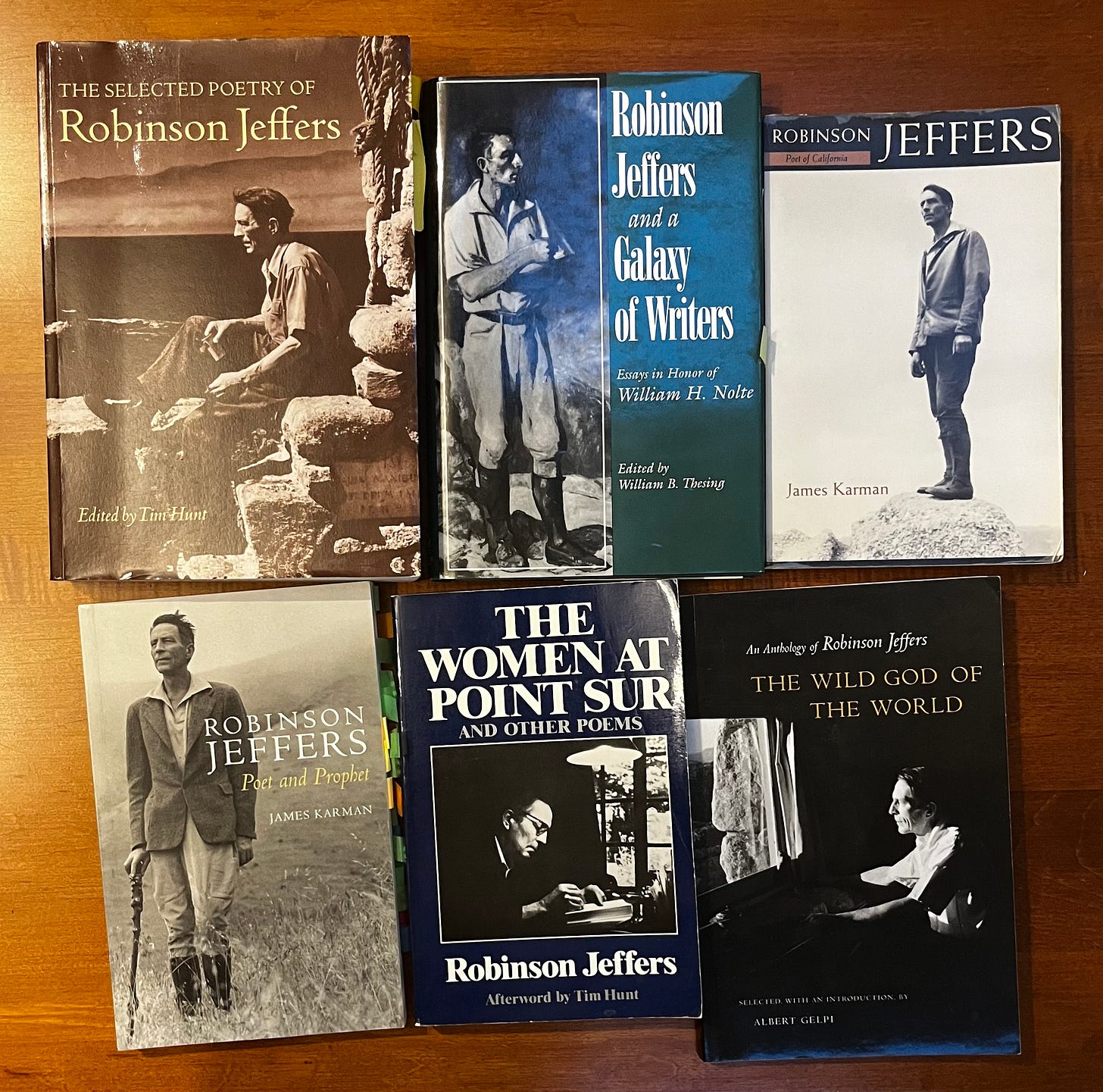

What does “disorder” look like? My area of disorder is actually quite orderly—often a pile of Robinson Jeffers. Selected Poetry, and a smaller collection of Selected Poems I am less reluctant to annotate. His letters and some criticism by academics; a sticky note with the email of an old professor I had, a Jeffers scholar, I’ll never email.

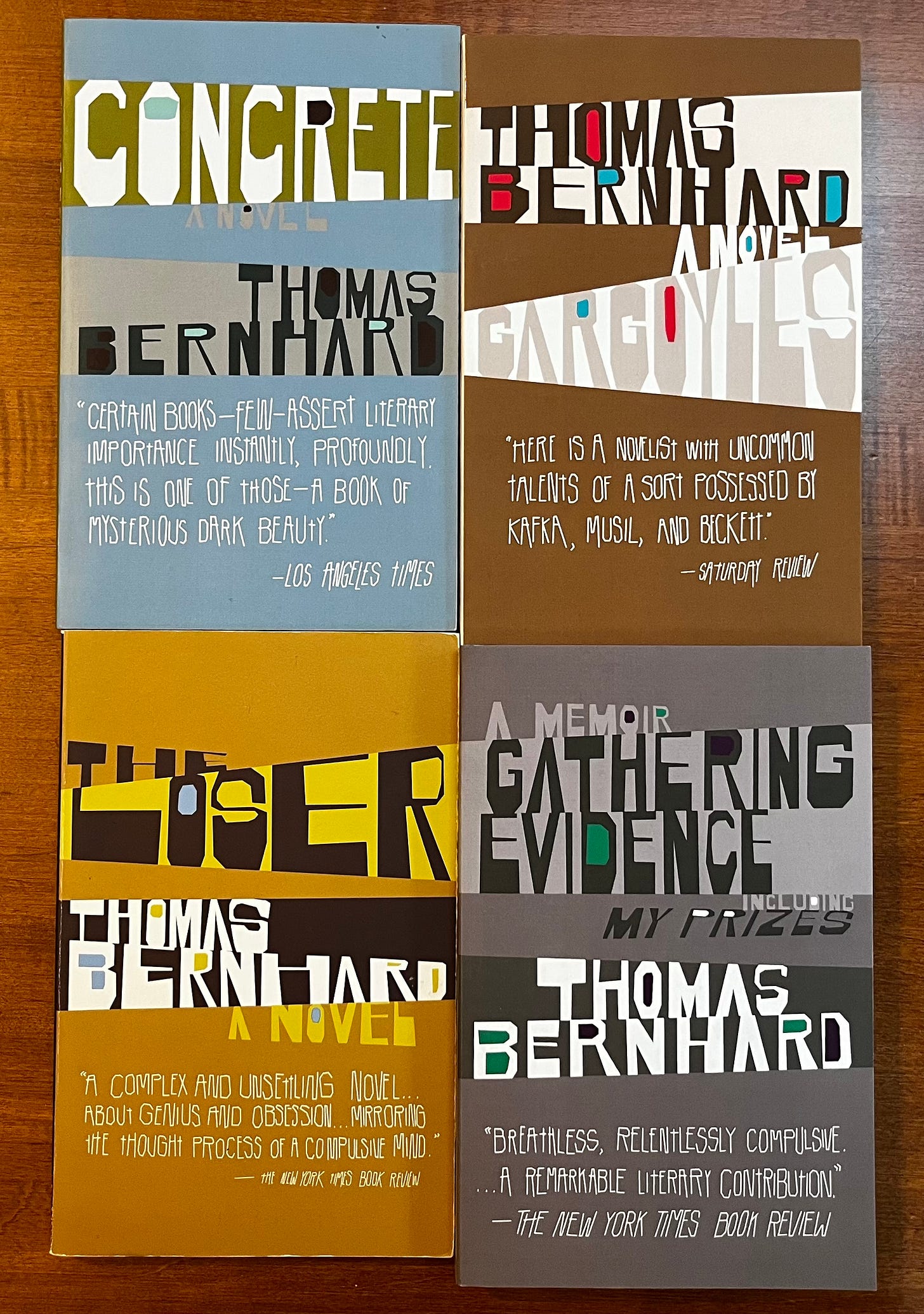

I’ve been “working” on something about Robinson Jeffers4 the way Rudolf, in Thomas Bernhard’s Concrete, is “working” on his study of Mendelssohn Bartholdy:

I assembled every possible book and article written by or about Mendelssohn Bartholdy. . . preparing myself with the most passionate seriousness for the task, which I had been dreading throughout the preceding winter, of writing—such was my pretension—a major work of impeccable scholarship.

My books and resources are there should I feel moved to write about Jeffers, however unlikely. The realm of disorder, “works in progress,” is not in-progress at all. It’s as idle as the realm of order—hence, relatively orderly.

Orderly or disorderly, collections become part of a “scene.”

Other elements of my scene include a pile of “great works.” Lots of Russians. Next to that is Seppala: Alaskan Dog Driver, a pile of books about sled dogs, and a manila folder of articles about Greenland.

I doubt the Seppala book, charmingly obscure, will ever be too useful. Frederik Sjöberg, in The Fly Trap, writes of the obscure A Bibliography of the Entomology of the Smaller British Offshore Islands, “I am always…exhilarated when I see it.” The Seppala book’s peculiar specificity makes it stick out, to quote Sjöberg again, “as if it somehow justifies my existence.”

The collector is obsessive—a bit off. He not only justifies the accrual of mostly superfluous objects, but often at great financial cost. Collecting gives him purpose.

To say the collector collects merely for collection’s sake is reductive. I’ve found I collect blank paper—journals, notebooks, legal pads—when I want to be productive. I derive enjoyment, but also practical purpose, from getting notebooks. They sit there and demand to be filled; I write about my day, transcribe a poem, make a to-do list.

Collecting books, I succumb not to boredom but anxiety. Is there something I ought to be reading? Whatever I’m currently reading can’t be it. I rush obtain the book I ought to have been reading the entire time.

I might tell myself: I should be reading Solzhenitsyn! and go to the bookstore or an online vendor. Rarely do I get the intended Solzhenitsyn, but rather end up with a book I didn’t plan on. This is what I should’ve been reading all along, not Solzhenitsyn!

After long enough I come to the nauseating realization the new book is not my answer. There could be another book I ought to be reading. I finish the book, or if it hasn’t grabbed me I abandon it. Then it’s back on the hunt for the book.

I end up with a lot of books.

Geoff Dyer notes, in Out of Sheer Rage, certain books have value as objects. When packing for a trip—planning to begin, as he plans for the entire book, his study of D.H. Lawrence—he can’t decide whether to bring Lawrence’s Complete Poems.

The value of the The Complete Poems was talismanic: if I had it with me I would be able to begin my book; if I didn’t have it with me then, even if I did not need to refer to it, I would keep thinking that I did and would be unable to begin my book about Lawrence.

Dyer decides to leave The Complete Poems behind, then changes his mind. He captures the collector’s mindset: “If I take it I won’t need it; if I don’t take it I will not be able to get by without it.” The collector might not need more, but can’t get by without it.

To put so much stock in objects—books, stamps, what-have-you—can indicate a certain dissatisfaction with humanity, with normal, everyday life. Perhaps “dissatisfaction with” is too strong; let’s say “ambivalence toward.”

Rudolf’s sister, in Concrete, describes his home and library as a “morgue.” A collection of dead thinkers and old books he prefers to living thinkers and new ones.

Sjöberg’s collection is an actual morgue: boxes of dead flies.

The time Rudolf spends in his library, among the dead, has made him into a “sick, almost crazy, a sad, comic figure,” his sister says. The same can be said of the collector. The hoarding impulse can seem crazy, almost a disease.

I have packed, unpacked, culled, organized, and repacked my library into U-Hauls, vans, and trucks. I have unpacked, added to it, culled, and repacked it again. I have downsized, upsized, and reorganized it pretty much constantly.

It is something I’m always doing and will never be done with.

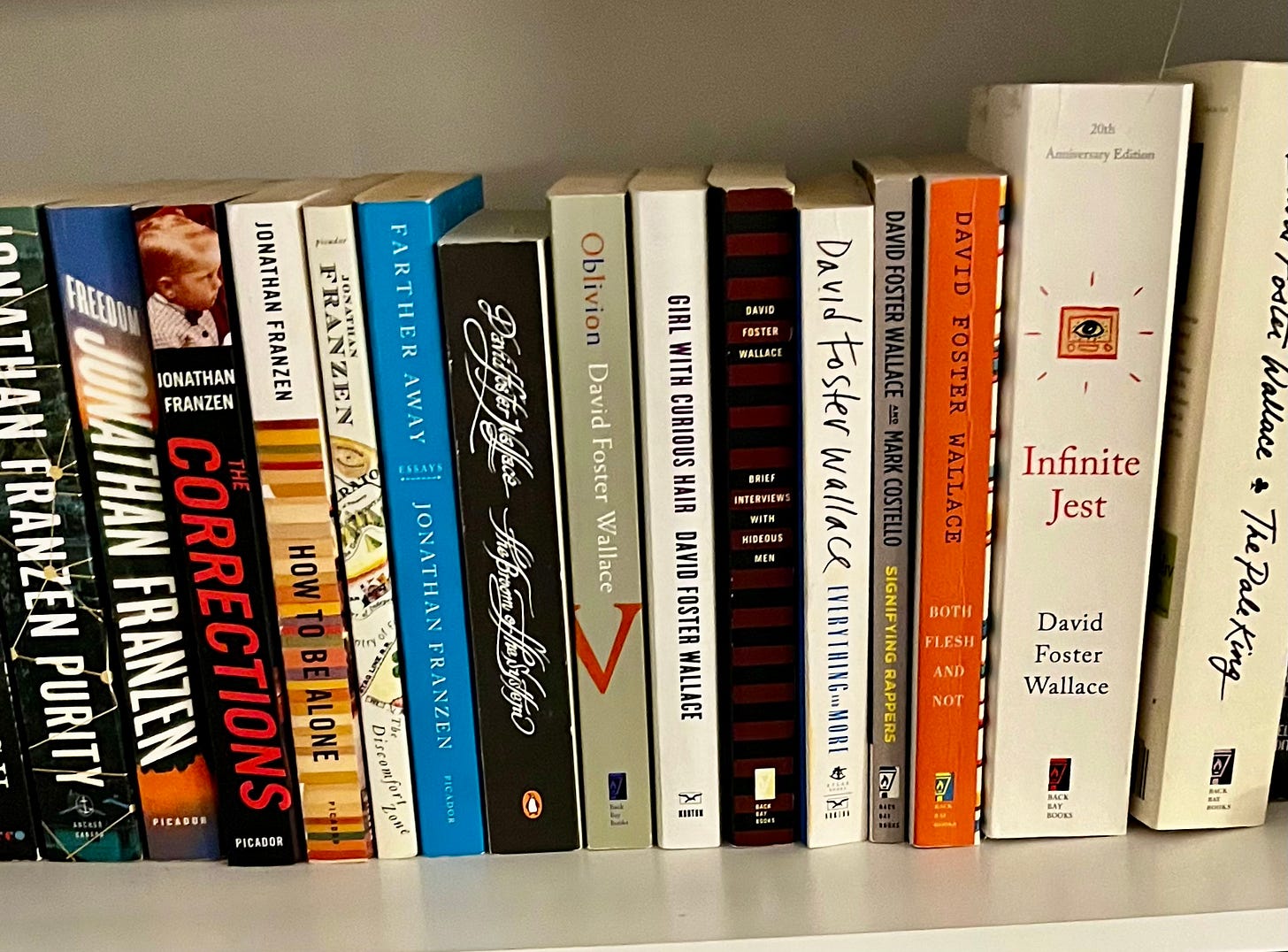

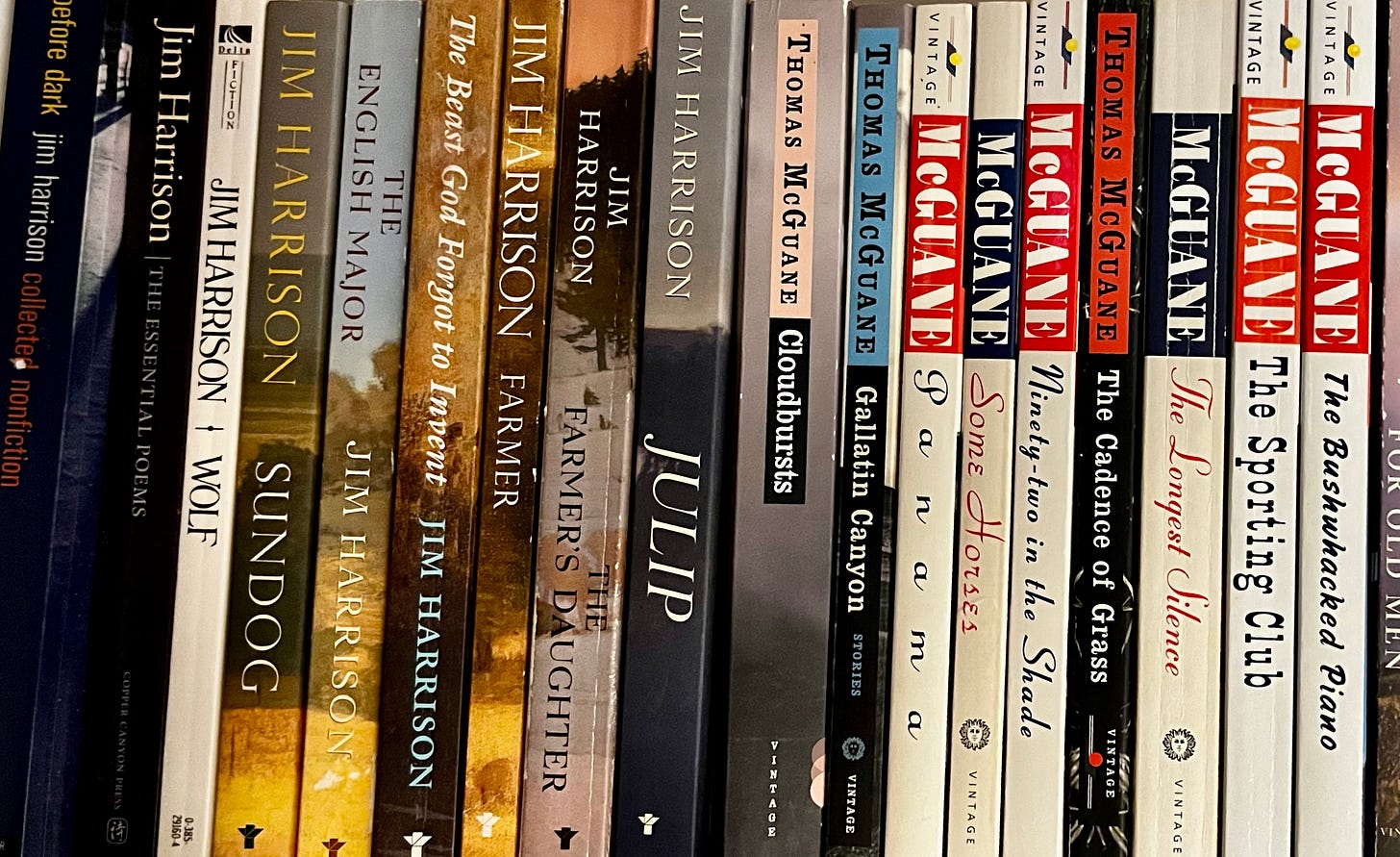

McGuane and Harrison, Wallace and Franzen.

Russell Banks, Ron Rash, J.G. Ballard, others. I’d taken a college course with one of his favorites, Ron Hansen.

Twice I registered for a week of wooden boatbuilding courses, but was unable to partake each time. Before I die, I will build a lapstrake dory.

When I debated a PhD, Jeffers was a big part.

So awesome, James. Reviewing this rich list will take me awhile. Looking forward to the adventure.

Really eclectic and amazing collection of books, James. "Grizzly Years" by Doug Peacock is one of my favourites. I will gave to check out the "Against Civilization" book. I'd heard about it and have not yet read it.

I have given away and reduced my own collection over the past few years. It was a difficult thing to do, but ultimately I feel lighter mentally somehow - hard to explain.