A New Reality

These ongoing years of traumatic brain injury recovery have been educational. I’m not glad it happened, but it sparked good changes in how I move through the world.

My TBI is not representative of all TBIs. No TBI is. I’m lucky, but indubitably have and constantly navigate a diffuse axonal brain injury. A few months ago a doctor described my disability, still, after three years, as severe. I’m also lucky. Upon reviewing an MRI of my brain when I still wasn’t conscious, a different doctor called my injury a miracle. There were areas of my brain she expected to be worse. When I learned she said that, it put my feet to the fire—I don’t want to waste my luck.

Acceptance

Accept and learn from unfortunate realities. An essay by

in introduced me to “antifragility.”“Being antifragile means not just coping with stress but actually becoming stronger and more capable because of it.”

Reality is less stressful when we don’t run from it. In avoiding a stressful situation we might convince ourselves it’s worse than it is. Rather than worry about how bad something could be, base reactions in truth.

Deconstructing Obstacles

If the cause of your stress is too daunting, deconstruct it. Confront each element, get to know them, then confront all at once. TBI feels more manageable when I do this.

My balance is worse, when I work on it I think of nothing else. I have no shortage of symptoms but when it’s time to work on balance it’s the only one.

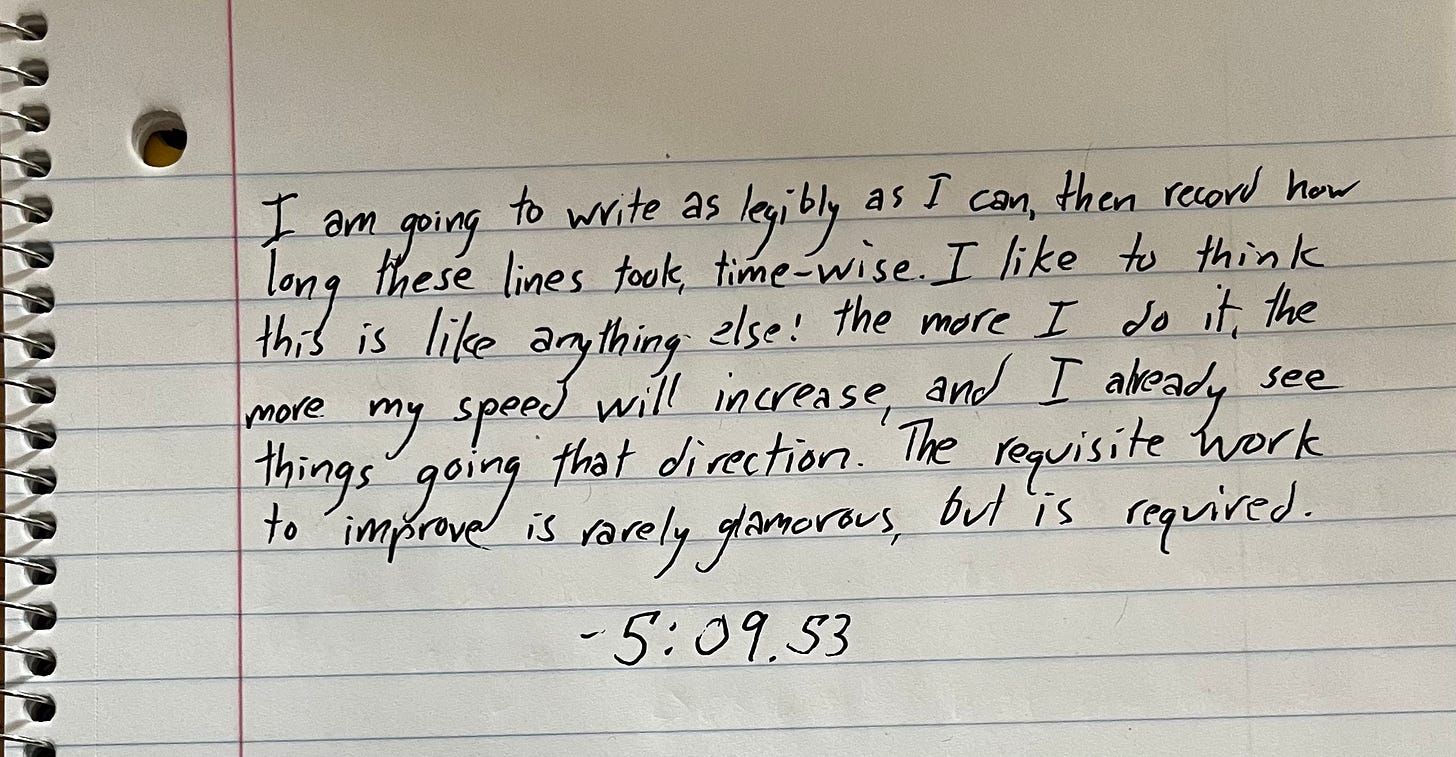

writes, “Balance…like anything else, can be trained.” I train mine and see improvement.Writing by hand is also difficult for me. When I practice, I focus only on that aspect of my disability. To not worry about my vision, I wear an eyepatch. Often I forgo one so my eyes can try to collaborate—though I just bought a leather one to wear more often—but writing on lined paper challenges my diplopia. I don’t want to be distracted. It’s been years I’ve worked on writing by hand, I wrote about it at the end of 2022:

I’m quite slow, not that neat. Taking down a message while on the phone is not nothing.

Im quicker and neater, but there’s still work to do.

Writing by hand is slow to improve, so I deconstruct. One session I’ll focus on speed; another, legibility. When I feel good I try both at once.

After my accident I atrophied forty pounds. Regaining weight was a priority. I’ve been a meathead for a while so was at the gym every morning. With time, lifting, and tubs of greek yogurt, I gained sixty pounds in three years. An overcorrection. I wanted to temporarily reach a bodyweight I was a decade ago and squat an amount of weight to show myself I could. I did, that’s finished now so I’ve lost fifteen pounds.

At the gym an embarrassing amount, I tried not to shy away from movements that were harder because of TBI-induced weakness (squats), lack of control of my right side (overhead press), bad balance (single leg RDLs), and right hand grip strength (hanging leg raises). When I loudly failed squats, it was met with encouragement from people who had no idea about my TBI. Failure happens in weight rooms. Did I fail because of my injury or did I just try too much weight? It doesn’t matter.

Goals & Change

Physical change is easy to understand. I had to change in other ways too, needed a new direction and got one. We each need a raison d'être. Maybe it’s fighting unwanted truths. Denial is passive, you convince yourself suboptimal truths are false and continuously sell yourself fictions to remain swaddled in them. Refusal is active. You combat or correct truths, requiring acknowledgement and acceptance. Different from resignation, acceptance of a truth can motivate you to change it.

Recovering from my injury forced me to be patient. Do I want to wake up one day and see properly? Of course. The reality is it requires years of waiting, there’s no guarantee I’ll ever have correct vision again but I remain hopeful. It’d be draining to feel deflated every time I’m reminded of my vision problem—whenever I use my eyes.

Do I want to jot down notes when talking on the phone? Yes, but I haven’t jotted in years. It’ll take more time and handwriting training. As with vision, there’s no guarantee I’ll ever jot anything down again—but no reason not to try.

Patience is something I’ll always work on; its inescapable necessity gives me plenty of opportunity. When you acquire speech difficulty as I did, you have to slow down. It doesn’t matter how excited you are to say what you want to say. If excitement would’ve manifested as speed, let it instead be clarity. Trade cascading ebullience for measured precision, a new layer to “think before you speak.”

Reframing

With reason to be pessimistic, choose the opposite. Hope for and facilitate the best—sometimes even cautiously expect it. If proper steps are being taken, there’s no reason not to.

Restarting after an event like a traumatic brain injury, choices made, actions taken or not taken, and their repercussions become undeniable. Contrary to the above-mentioned right steps, sometimes they might’ve been wrong.

Why didn’t I do that? Why did I? How was I happy with that choice?

Choices that didn’t seem it at the time might’ve been mistakes. Hindsight is 20/20. Accept missteps and learn from them so you don’t make similar mistakes again.

I always chose to find negatives, now I choose positives. Don’t naively expect everything will go your way but when it doesn’t, reframe.

An employer didn’t hire you, even with your impressive resume, extensive experience, and strong interview.

You weren’t right for them. Were they right for you? Find something else. Maybe it’ll pay better or give you a reason to relocate. Maybe it’s time to make a change. Eventually you’ll think of this job you didn’t get and be thankful you didn’t.

Your partnership ended.

Whether you left or were left it’s going to hurt, but try to see it as a good thing. Emphasis: try. It will likely hurt for a while. If you left, you did the hard but probably right thing. If you were left, it hurts. Things will get better. Eventually, similar to that job you didn’t get, you’ll think about where you’d be had it not ended. That’s what I wanted? It’ll take time, but you’ll feel thankful things ended.

You interviewed for half-a-dozen jobs in the same field you’ve worked in for years, but none panned out.

Common denominators: The field and you. Don’t keep trying in the wrong field for you. Maybe you’re a square peg and those jobs were round holes.

What are you good at? What do you like? Do something else. Half-a-dozen job rejections is a rude awakening, but still an awakening.

Abilities

I’ve become happy with less.

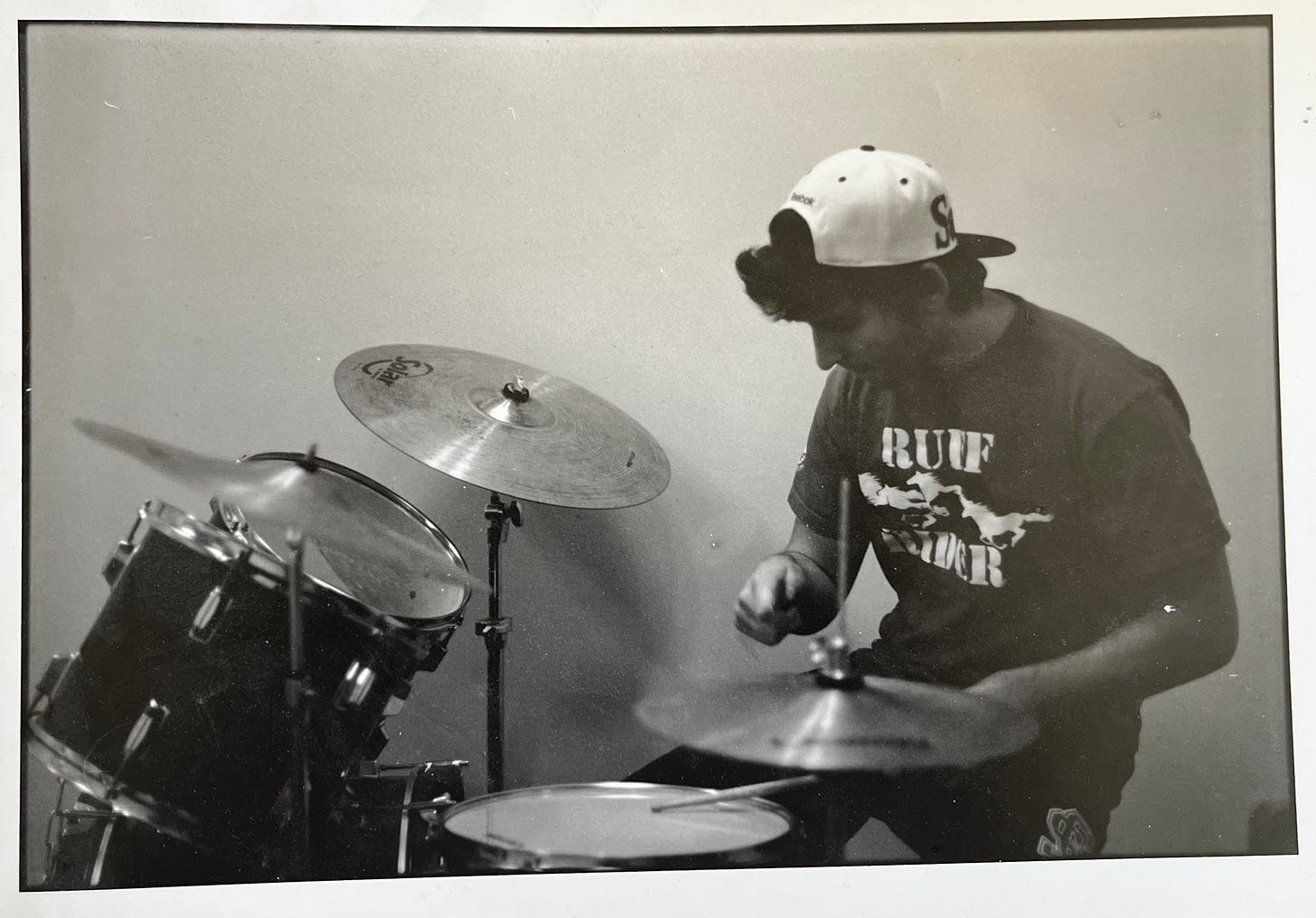

Before my TBI I was a good drummer. I’m not anymore. Gross and fine motor impairment make me less able to control a drumstick.

TBI survivor, artist, and advocate Alison Rheaume says not to feel pressured to regain abilities just because you feel like you should. There’s no “expectation that you have to do it again if you don’t want to.”

Rheaume advises, “honor that you tried and let yourself feel what comes up.” I’m not as good at drumming so won’t play in the same way or try to. When I infrequently pick up the sticks I have realistic expectations. I was already playing less, but could have if I wanted to.

It’s fun to drum for “Impressions” or to do John Bonham triplets. Now I’m happy with less, paradiddles or flam accents on a practice pad. I’ll still drum, less often, but don’t predict ever being happy with my ability again.

Rheaume says, “celebrate how good you were before; you still accomplished that in the past.” Watching old videos of me drumming makes me emotional. It’s important to “allow yourself to grieve the loss,” she suggests. I also reframe. Since I won’t get drumming back, I can try new things.

Fly fishing is not a new thing, and not something I’ll give up—even though I lost ability. It’s been regained more than drumming.

Can I double haul with a nine weight on a windy evening to a distant rock for striped bass (Morone saxatilis)? Not as well. Happy with less: a 40 foot cast with my four weight to chain pickerel (Esox niger), whose “body resembles a barracuda’s and has evolved to similar purpose,” writes John McPhee.

It doesn’t matter if I can’t fish as well; it matters that I can and do in modified ways, with self-granted accommodations. Happy with less—less skill, less frequency, less importance to my identity—but still happy.

I love fishing, but I love more than a bend in my rod. The places it takes me, reading Gierach, McGuane, Maclean, fishing with others, just being outside. I share what I know with new anglers and get to relearn alongside them, but also fish with those who know I lost abilities but reassure me not to stop.

“My” TBI

I’ve come to accept this traumatic brain injury as “mine.” I didn’t call it that before, I wrote in The Invisible Injury that calling it that gave it ownership of me.

Calling it mine actually, obviously, expresses the opposite. I own it. I’m comfortable enough with my reality that I tell people, despite not appearing to be, “I’m disabled.”

Years are BC, Before Christ, or AD, Anno Domini. Mine are BTBI and ATBI, before and after. Having grieved, I’m moving into ATBI years with hope and positivity.

I survived the accident, but in an abstract way I died. ATBI me is different in good ways. I’m thankful for so much. My luck, my family, people in my life, my inherited stubbornness. I’m excited for what is to come.

The ability to reframe is a superpower, James. I love how you lean into that. Thank you for this one.

You make great points about Denial being passive vs. Refusal being active. I like that way of looking at challenges. I am learning about TBI from your posts on the subject and this is not something I knew anything about. Thanks for sharing, James.